NASA’s recent tests to design a technique that would allow additive manufacturing to create durable 3-D rocket parts made with more than one metal show great promise for the technique to eventually replace the brazing process.

Engineers at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, tested NASA’s first 3-D printed rocket engine prototype part made of two different metal alloys through an innovative advanced manufacturing process. NASA has been making and evaluating durable 3-D printed rocket parts made of one metal, but the technique of 3-D printing, or additive manufacturing, with more than one metal is more difficult.

“It is a technological achievement to 3-D print and test rocket components made with two different alloys,” said Preston Jones, director of the Engineering Directorate at Marshall. “This process could reduce future rocket engine costs by up to a third and manufacturing time by 50 percent.”

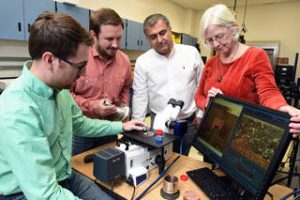

Engineers at Marshall, led by senior engineer Robin Osborne, of ERC, Inc. of Huntsville, Alabama, supporting Marshall’s Engine Components Development and Technology branch, low-pressure hot-fire tested the prototype more than 30 times during July to demonstrate the functionality of the igniter. The prototype, built by a commercial vendor, was then cut up by University of Alabama–Huntsville researchers who examined images of the bi-metallic interface through a microscope. The results showed the two metals had inter-diffused, a phenomenon that helps create a strong bond.

A rocket engine igniter is used to initiate an engine’s start sequence and is one of many complex parts made of many different materials. In traditional manufacturing, igniters are built using a process called brazing which joins two types of metals by melting a filler metal into a joint creating a bi-metallic component. The brazing process requires a significant amount of manual labor leading to higher costs and longer manufacturing time.

“Eliminating the brazing process and having bi-metallic parts built in a single machine not only decreases cost and manufacturing time, but it also decreases risk by increasing reliability,” said Majid Babai, advanced manufacturing chief, and lead for the project in Marshall’s Materials and Processes Laboratory. “By diffusing the two materials together through this process, a bond is generated internally with the two materials and any hard transition is eliminated that could cause the component to crack under the enormous forces and temperature gradient of space travel.”

For this prototype igniter, the two metals–a copper alloy and Inconel–were joined together using a unique hybrid 3-D printing process called automated blown powder laser deposition. The prototype igniter was made as one single part instead of four distinct parts that were brazed and welded together in the past. This bi-metallic part was created during a single build process by using a hybrid machine made by DMG MORI in Hoffman Estates, Illinois. The new machine integrated 3-D printing and computer numerical-control machining capabilities to make the prototype igniter.

While the igniter is a relatively small component at only 10 inches tall and 7 inches at its widest diameter, this new technology allows a much larger part to be made and enables the part’s interior to be machined during manufacturing—something other machines cannot do. This is similar to building a ship inside a bottle, where the exterior of the part is the “bottle” enclosing a detailed, complex “ship” with invisible details inside. The hybrid process can freely alternate between freeform 3-D printing and machining within the part before the exterior is finished and closed off.

“We’re encouraged about what this new advanced manufacturing technology could do for the Space Launch System program in the future,” said Steve Wofford, manager for the SLS liquid engines office at Marshall. “In next-generation rocket engines, we aspire to create larger, more complex flight components through 3-D printing techniques.”