Improving Hardening and Introducing Innovation for In-House Heat Treat

Digital tools lead the way in vacuum hardening operations to ensure energy efficiency and processing repeatability. In this Technical Tuesday installment, Paulo Duarte, project manager at Metalsolvus, examines various advantages of wrought versus cast alloys in heat treat operations.

This informative piece was first released in Heat Treat Today's March 2025 Aerospace print edition.

Vacuum hardening has been the chosen process for hardening tools used in plastic injection, die casting, and metal sheet stamping over the past few decades. Although widely used and accepted, there is still room for improvement in tool performance through quality driven procedures. By employing easy methods of measurement, study, and testing, it is possible to enhance part integrity and mechanical properties, while simultaneously reducing heat treatment time and energy consumption. Advanced metallurgical analyses of heat treatment cycles and equipment can introduce better tools on the market, as well as provide time and cost saving heat treatments.

Basics of Vacuum Hardening

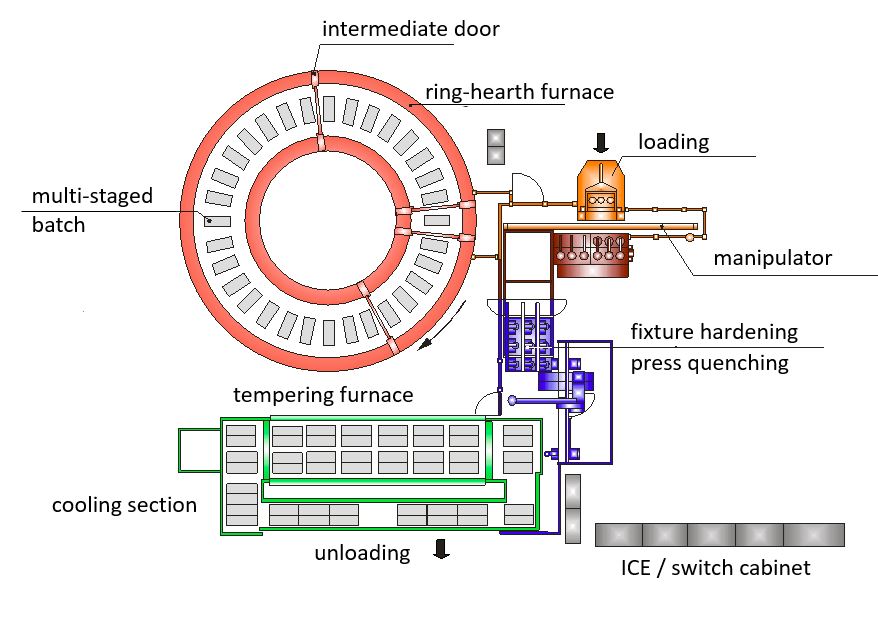

In vacuum hardening furnaces, temperature and time are carefully controlled at specific load locations to ensure optimal hardening. Optimal practices focus on heating and soaking the metal parts during heat treatment. The controlled introduction of vacuum and inert gases during the process ensures the right protective atmosphere for treatment, resulting in steel that is mainly free from oxidation and decarburization. This preserves the surface integrity of the tools.

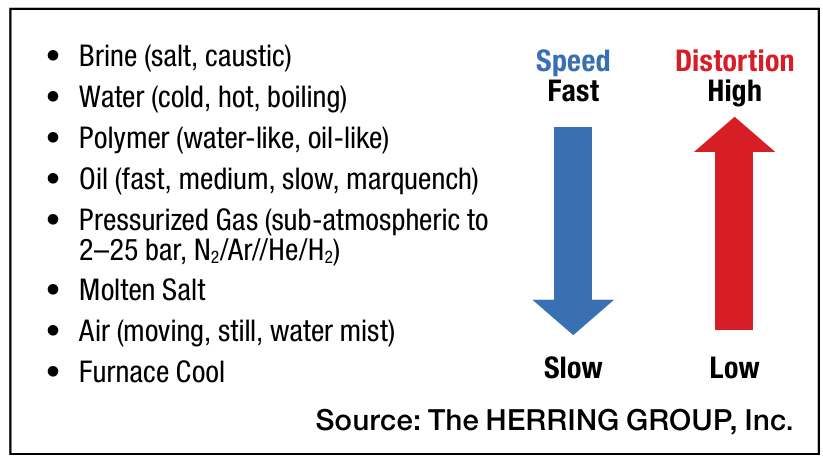

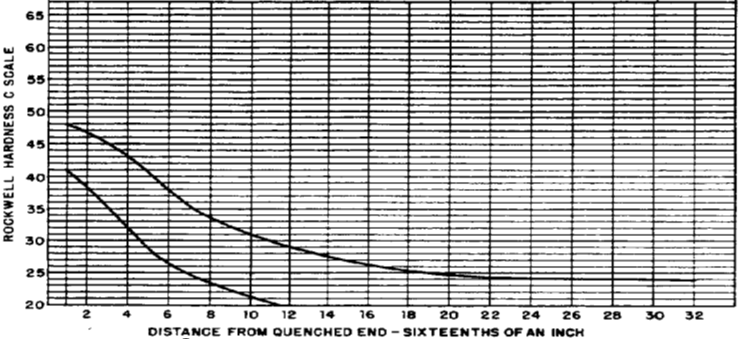

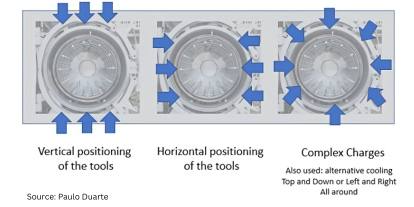

Cooling is achieved through the injection of an inert gas into the heating chamber, with controlled pressure and adequate recirculation between the heat exchanger and the hot zone (Figure 1). Different gas injection directions are utilized depending on the load being treated, ensuring optimal cooling.

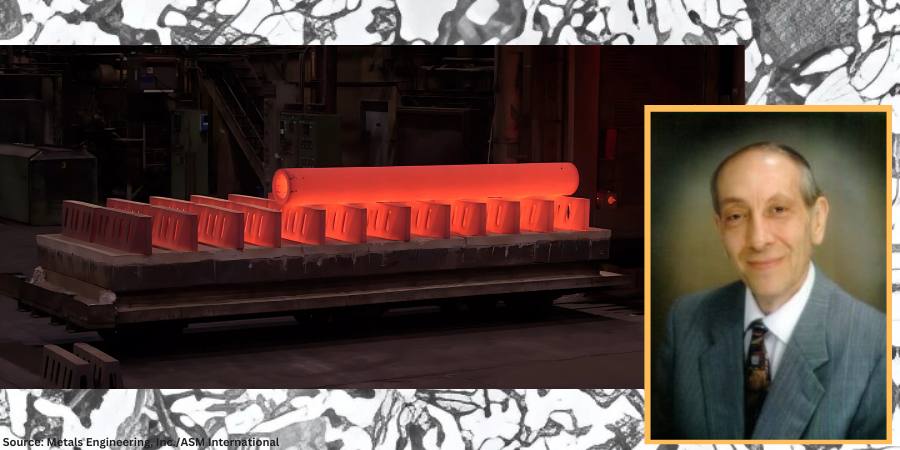

Hardening of Large Tools

Heating and quenching large tools is one of the most challenging situations for vacuum hardening, as temperature control and part microstructure integrity are more difficult to obtain, which affects part quality. Large tools, typically made of hot work tool steels, are hardened in large furnaces. To minimize deformation, parts are preferably positioned vertically inside the furnace (Figure 2).

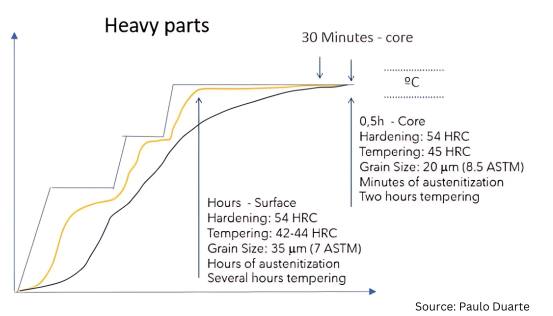

Surface soaking times for big tools can significantly exceed

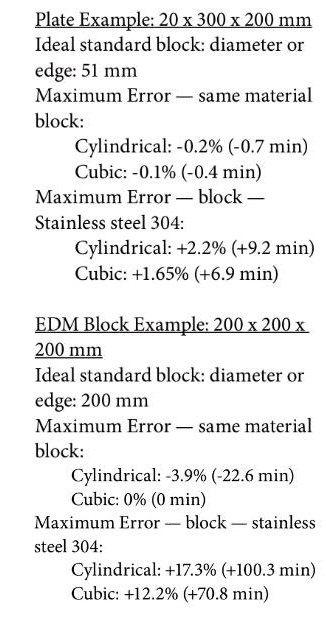

standard austenitization and tempering times due to thermal gradients existing within the parts. Mold cores usually achieve the right soaking and tempering recommendation through accurate temperature control, monitored by well-positioned core thermocouples. A tool’s microstructure and performance will depend heavily on geometry, size, and temperature uniformity achieved during treatment. See Figure 3 for the core and surface typical hardening cycles for large tools.

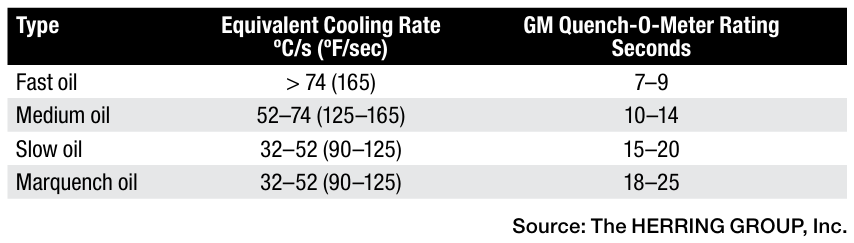

The cooling phase is crucial in determining the final properties of both the surface and core of the tool. Higher gas injection pressures result in faster cooling and increased toughness, but this also introduces greater deformation risks, when directly cooled from austenitization temperature, so martempering done at low pressures is usually required.

Balancing cooling pressure is one of the most secret topics in vacuum hardening. With a variety of parameters and procedures used among heat treaters, measuring and testing is essential for achieving consistent quality for better controlling the hardening process and attaining the best part quality.

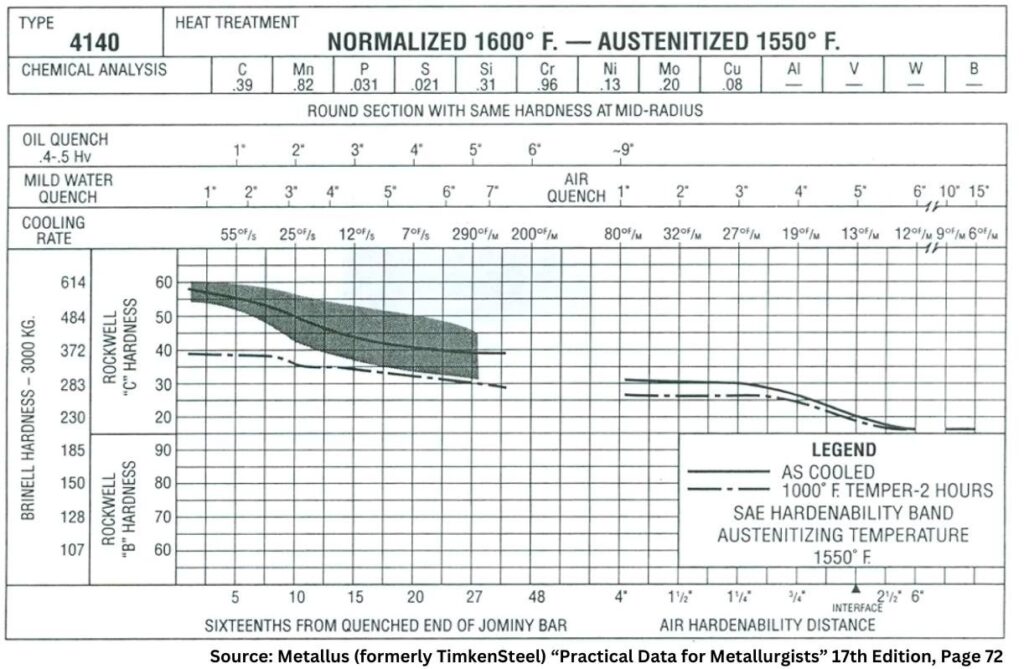

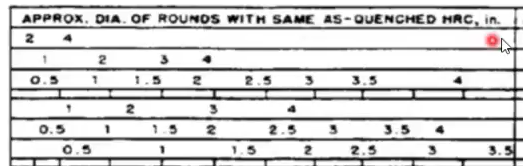

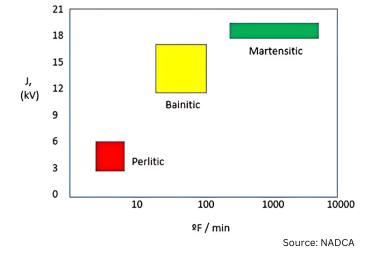

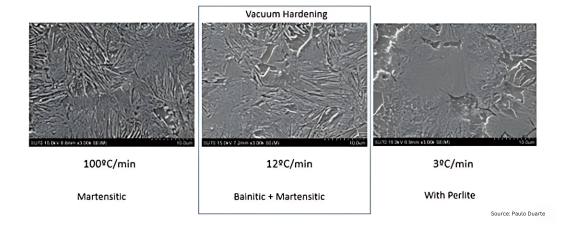

The use of higher or lower inert gas pressures directly affects the cooling rate, making it faster or slower, respectively. Regulating the gas injection pressure during the cooling phase significantly impacts the material’s toughness, even when cooling occurs within the bainitic-martensitic domain commonly observed in vacuum hardening practices. Faster cooling leads to finer microstructures, which in turn results in tougher materials. However, fully martensitic microstructures are rarely achieved in industrial vacuum hardening furnaces and are typically limited to smaller loads composed of small parts. In larger parts, the risk of pearlite formation increases, especially when cooling rates fall around 3°C/min (5°F/min) at the core, as illustrated in Figures 4 and 5.

In industrial heat treatments of large tools, accurately monitoring core temperature is challenging, as it is difficult to position a thermocouple hole exactly at the innermost location or a nearby region. This makes it harder to control the hardening process and prevent pearlite formation. Therefore, studying the process to establish effective control measures is essential for achieving the highest possible

quality.

Heat treatment simulation simplifies this task by allowing the hardening process to be predicted, with thermal gradients estimated and compensated through furnace control parameter adjustments. Figure 6 presents a real case study, where the temperature distribution inside a large mold was fully characterized during the entire heat treatment cycle using FEM (finite element method) simulation and validated through actual thermocouple measurements. FEM simulation, as a proven and highly effective technique for predicting heat treatment cycles, enables heat treaters to implement optimized, computer-supported heat treatment practices.

Vacuum Hardening Standard Block Size and Cycle Forecast

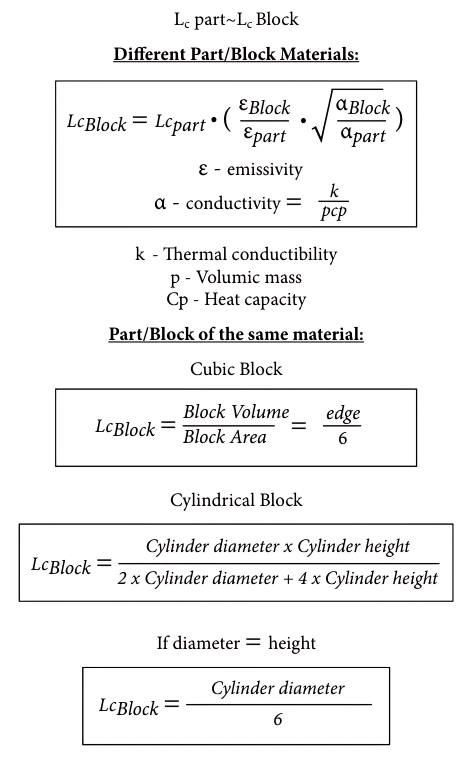

When working with loads composed of small to medium-sized parts, the core temperature of the load can be monitored using dummy standard blocks. These blocks have a central hole to accommodate the thermocouple used to control the heat treatment cycle. The dummy block should be selected to closely match the size of the largest part in the load. However, in commercial heat treatment settings, part sizes can vary widely, making it difficult to maintain a comprehensive set of dummy blocks that represents all possible heat treatment scenarios.

Once again, simulation proves valuable in helping heat treaters gather useful data to anticipate the heat treatment cycle and determine the appropriate range of dummy blocks to have available on the shop floor. The procedure for selecting the dummy block range and forecasting the corresponding heat treatment times is outlined in the following equations. Ideally, the standard block should be made from the same material as the largest part in the load. If the materials differ, the characteristic length of the block can be calculated using the first of the equations to the right.

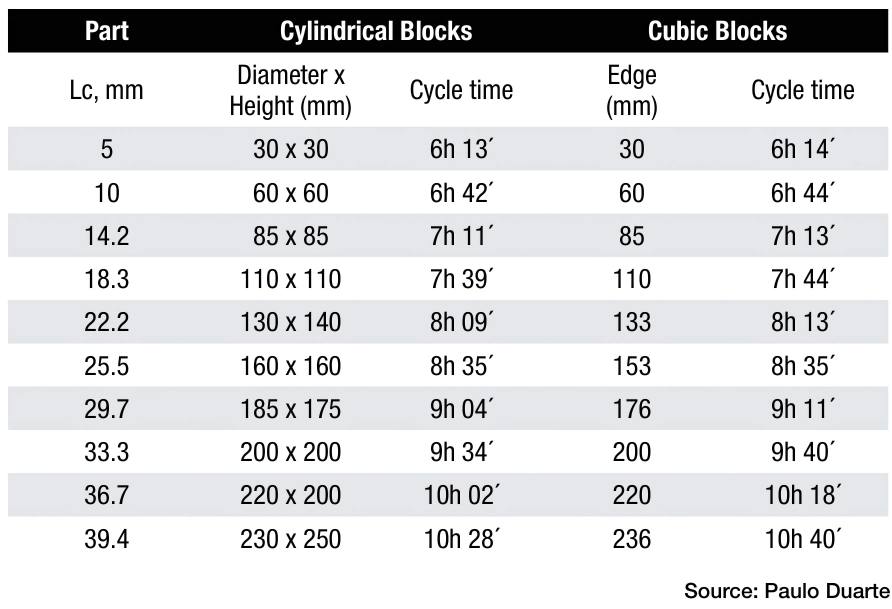

Table 1 lists a range of proposed dummy block sizes to be used for monitoring the load temperature during heat treatment. The time to end of soaking at higher temperature is also given by Table 1 for a typical 600 x 600 x 900 mm hardening furnace. Times were obtained by FEM simulation and can be used to forecast the end of austenitization in a hardening process of each dummy block.

The simulated times were validated by using real parts temperature measurement by thermocouples. These were the calculated errors based on simulation and heat treat validation trial:

Optimizing the Vacuum Hardening of Tools

FEM simulation can also be used to optimize the heat treatment process, but metallurgical testing remains crucial for providing reliable insights into safely reducing cycle time and energy consumption. Typically, for setting the isothermal stage time, a tolerance of -5°C relative to the temperature setpoint is used, leading to savings in both heat treatment duration and power consumption, as shown in Figure 7a. However, Figure 7b demonstrates that higher tolerance values (ΔT) can be considered. Tolerances of up to -10°C or even -20°C can be applied for controlling the soaking time without significantly affecting the hardness and toughness of the parts. Naturally, these results depend on the desired setpoints for the isothermal stages, but Figure 7c reflects the worst-case scenario for ΔT, referring to the use of lower austenitizing and tempering temperatures commonly applied in the hardening of hot-work tool steels.

Future Trends of Vacuum Hardening

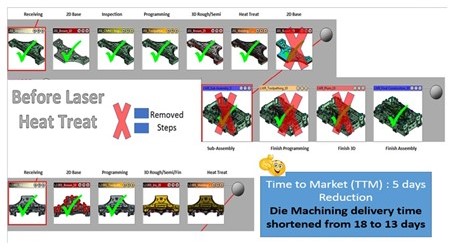

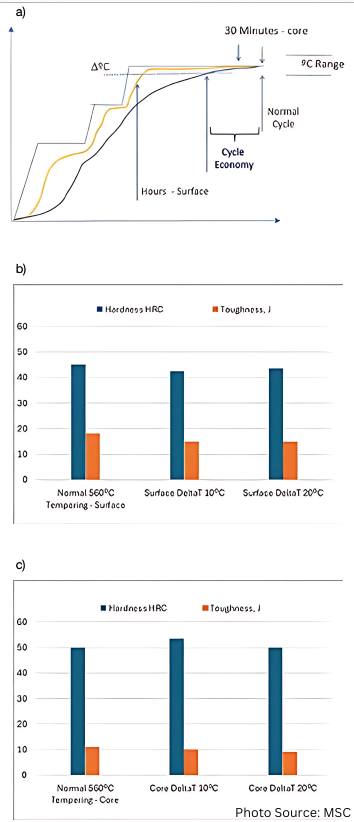

Innovations like digitalization, automation, and resource reduction, as part of Industry 5.0 initiatives, are expected to drive advancements in heat treatment processes. Long martempering, a heat treatment under development for hardening hot-work tool steels, shows promise as an alternative to traditional quenching and tempering. This process offers a balance of high hardness and toughness in significantly less time, providing energy savings and faster turnaround.

New Vacuum Hardening Process — Long Martempering

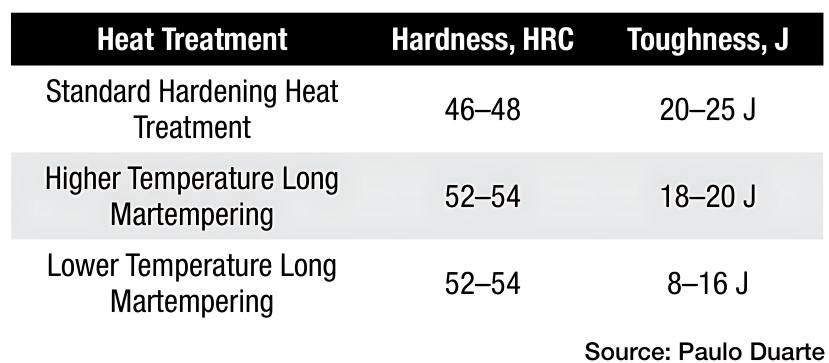

Long martempering is a heat treatment under development that can be used to harden hot-work tool steels. Long martempering is a process somewhat similar to austempering but is applied to steels rather than cast irons. Performed at temperatures within the martempering range, long martempering corresponds to an interrupted bainitic heat treatment with a specific process window (Figure 8) where high toughness is achieved at hardness levels exceeding those obtained through traditional quenching and tempering. Table 2 lists the mechanical properties attained for 5Cr hot-work premium tool steels.

The transformation during long martempering is not yet fully characterized in terms of microstructure, however, curved needles of bainitic ferrite are observed without carbide precipitation. This phenomenon is generally not associated with steel but rather with ausferrite in cast irons. Nonetheless, it is evident in at least H11 and H13 premium steel grades. This one day martempering treatment could potentially replace the traditional two- to three-day heat treatment cycle for large tools, offering significantly faster lead times and reduced energy consumption. Moreover, the mechanical properties achieved through long martempering are notable, as high levels of both hardness and toughness are obtained simultaneously, as demonstrated in Table 2.

Industry 5.0

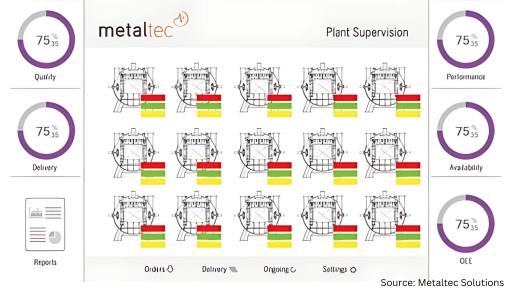

The integration of heat treatment equipment with management software enhances furnace utilization, quality control systems, and maintenance practices. Industry 5.0 can be implemented in heat treatment plants through the connection of databases that collect inputs from furnaces (e.g., temperature, time, pressure, heating elements, and auxiliary equipment performance) and production data (e.g., batch numbers, order details, operator information, cycle setup, and load weight). This data is analyzed by software to generate valuable insights for plant management, process optimization, predictive maintenance, and quality control.

A supervision interface for a 5.0 solution can monitor furnaces and control them remotely in real time (Figure 9). Operators receive updates on tasks, alerts, and production schedules. Additionally, plant productivity, efficiency, and maintenance can be tracked through the same supervision software, whether on site or remote. Automatic reporting is also possible, enabling the approval or rejection of cycles based on criteria that are not typically used in heat treatment plants. This not only improves quality but also facilitates process optimization and cost reduction.

Conclusion

Acquiring a full understanding of furnaces in operation through data measurement and analysis allows full control over the heat treatment process. This facilitates process development, enabling cycle optimization and improvement in part quality. Additionally, testing and simulation practices can lead to cost reduction and shorter lead times.

The introduction of long martempering and Industry 5.0 will significantly enhance heat treatment processes, leading to improved delivery times and reduced operational risks. Automation and digitalization bring more data to the shop floor, improving plant management and resulting in greater efficiency, higher quality parts, and simplified task execution.

Finally, current personnel are busy with routine operations that are based on long established practices and may be limiting opportunities for innovation. Therefore, new teams or external consultants can be leveraged to focus on designing, studying, testing, and implementing each new heat treatment solution.

References

Fernandes, José, Laura Ribeiro, and Paulo Duarte. “Study of the Bainitic Transformation of H13 Premium Steel.” MSC thesis, Faculty of Engineering of Oporto University, 2021.

Figueiredo, Ana, Paulo Coelho, José Marafona, and Paulo Duarte. “Study of a Methodology for Selecting Standard Blocks for Hardening Heat Treatments.” MSC thesis, Faculty of Engineering of Oporto University, 2022.

Kind & Co. “Vacuum Hardening with Highest Levels of Precision.” Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.kind-co.de/en/company/technologies/vacuum-hardening.html.

Maia, Pedro, Paulo Coelho, José Marafona, and Paulo Duarte. “Study of Heating Stage of Big Dimensions Steel Parts Hardening.” MSC thesis, Faculty of Engineering of Oporto University, 2013.

Metaltec Solutions. “Brochure Presentation.” Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.metalsolvus.pt/en/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/plant-supervision-brochure-V3.pdf.

Miranda, Isabel, Laura Ribeiro, and Paulo Duarte. “Heat Treatment of AISI H11 Premium Hot-Work Tool Steel.” MSC thesis, Faculty of Engineering of Oporto University, 2024.

Pinho, José Eduardo, Gil Andrade Campos, and Paulo Duarte. “Modelling and Simulation of Vacuum Hardening of Tool Steels.” MSC thesis, Aveiro University, 2017.

Ramada. “New Hardening Furnace up to 4 Tons.” Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.ramada.pt/pt/media/noticias/novo-forno-de-tempera-vacuo---ate-4-tons-.html.

Schmetz. “Schmetz Heat Treatment Furnaces.” Accessed January 30, 2025. https://edelmetal.com.tr/en/heat-treatment-furnaces.

Schmetz. Sketch of the Cooling Process in the Vacuum Hardening Furnace: Schmetz Commercial Proposals Drawing – Metalsolvus Training Courses Documentation.

Seco/Warwick. Vector 3D Hardening Furnace Commercial Brochure.

Solar Manufacturing. “Solar Vacuum Hardening Furnace.” Accessed January 30, https://solarmfg.com/vacuum-furnaces-horizontal-iq-vacuum-furnaces.

Wallace, J.F., W. Roberts, and E. Hakulinen. “Influence of Cooling Rate on the Microstructure and Toughness of Premium Grade H13 Die Steels.” Transactions of the 15th NADCA Congress (1989).

About The Author:

Paulo Duarte, project manager at Metalsolvus, is a researcher and consultant on heat treat technologies. His education and expertise in metallurgy has culminated in several articles and patents. He was a former technical manager within bohler-uddeholm group for the Portuguese market and heat treatment manager with the same group. Currently, Paulo focus on helping heat treaters by providing innovative, more efficient, and profitable heat treatment services to companies.

For more information: Contact Paulo Duarte at paulo.duarte@metalsolvus.pt.

Find heat treating products and services when you search on Heat Treat Buyers Guide.Com

Improving Hardening and Introducing Innovation for In-House Heat Treat Read More »