Given changing ecological and economic conditions, carbon neutrality is becoming more important, and the heat treatment shop is no exception. In the context of this article, the focus will be on how manufacturers — especially those with in-house heat treat — can save energy by evaluating heating systems, waste heat recovery, and the process gas aspects of the technology.

This article, written by Dr. Klaus Buchner, head of Research and Development at AICHELIN HOLDING GmbH, was released in Heat Treat Today April/May 2024 Sustainable Heat Treat Technologies print edition.

Introduction

Uncertainties in energy supply and rising energy costs remind us of our dependence on fossil fuels. This underlines the need for a sustainable energy and climate policy, which is the central challenge of our time.

European policymakers have already taken the first steps towards a green energy revolution, and the heat treatment industry must also take responsibility. Many complementary measures, however, are needed that can be applied to new and existing thermal and thermochemical heat treatment lines.

Heat Treatment Processes and Plant Concepts

The heat treatment process itself is based on the requirements of the component parts, and especially on the steel grade used. If different concepts are technically comparable, it is primarily the economic aspect that is decisive, and not the carbon footprint — at least until now. Advances in materials technology and rising energy costs are calling for production processes to be modified.

Source: AICHELIN HOLDING GmbH

An example is the quenching and tempering of automotive forgings directly from the forging temperature without reheating, which has shown significant potential for energy and CO2 savings. Although the reduced toughness or measured impact energy of quenching and tempering from the forging temperature may be a drawback due to the coarser austenite grain size, this can be partially improved by Nb micro-alloyed steels and higher molybdenum (Mo) contents for more temper-resistant steels; it may also be necessary to use steels with modified alloying concepts when changing the process.1, 2 AFP steels (precipitation-hardening ferritic pearlitic steels) and bainitic air-hardening steels can also be interesting alternatives, since reheating (an energy-intensive intermediate step) is no longer necessary.

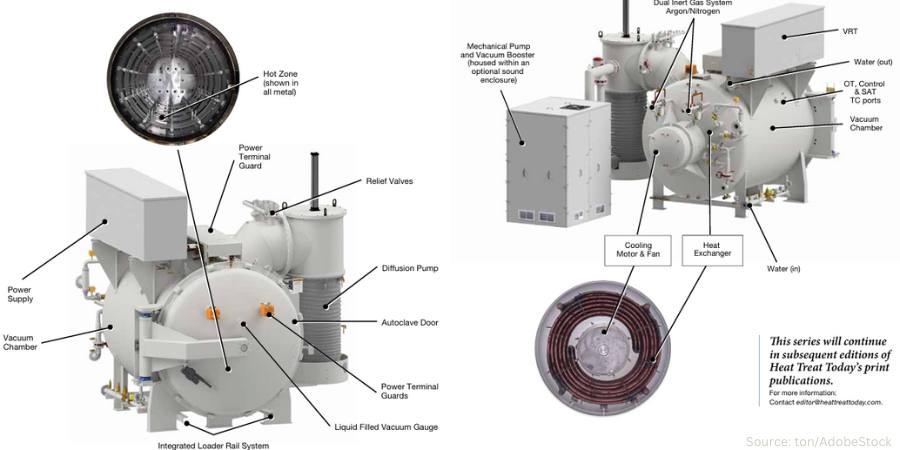

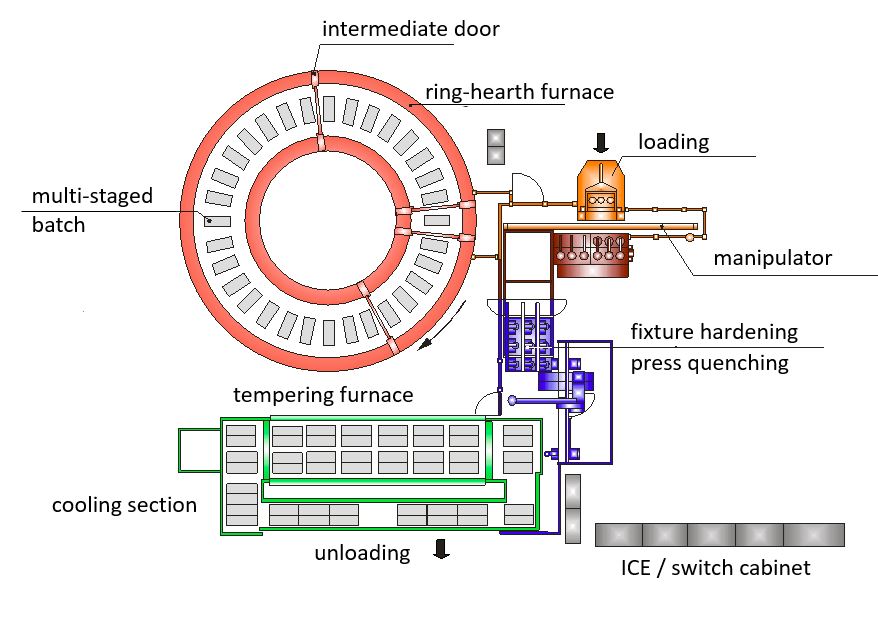

Similar considerations apply to direct hardening instead of single hardening in combination with carburizing processes because of the elimination of re-austenitizing. Distortion-sensitive parts often need to be quenched in fixtures due to the dimensional and shape changes caused by heat treatment. Heat treated parts are often carburized in multipurpose chamber furnaces or small continuous furnaces, cooled under inert gas, reheated in a rotary-hearth furnace, and quenched in a hardening press. In contrast, ring-shaped (aka donut-shaped) rotary-hearth furnaces allow carburizing and subsequent direct quenching in the quench press in a single treatment step. Figure 1 shows a typical ring-shaped rotary-hearth furnace concept for heat treating 500,000 gears per year/core hardness depth (CHD) group 1 mm.

Source: AICHELIN HOLDING GmbH

This ring-shaped rotary-hearth concept can save up to 25% of CO2 emissions, compared to an integral quench furnace line (consisting of four single-chamber furnaces, one rotary hearth furnace with quench press and two tempering furnaces as well as two Endothermic gas generators). Due to the reduced total process time (without reheating) and the optimized manpower, the total heat treatment costs can be reduced by 20–25%.

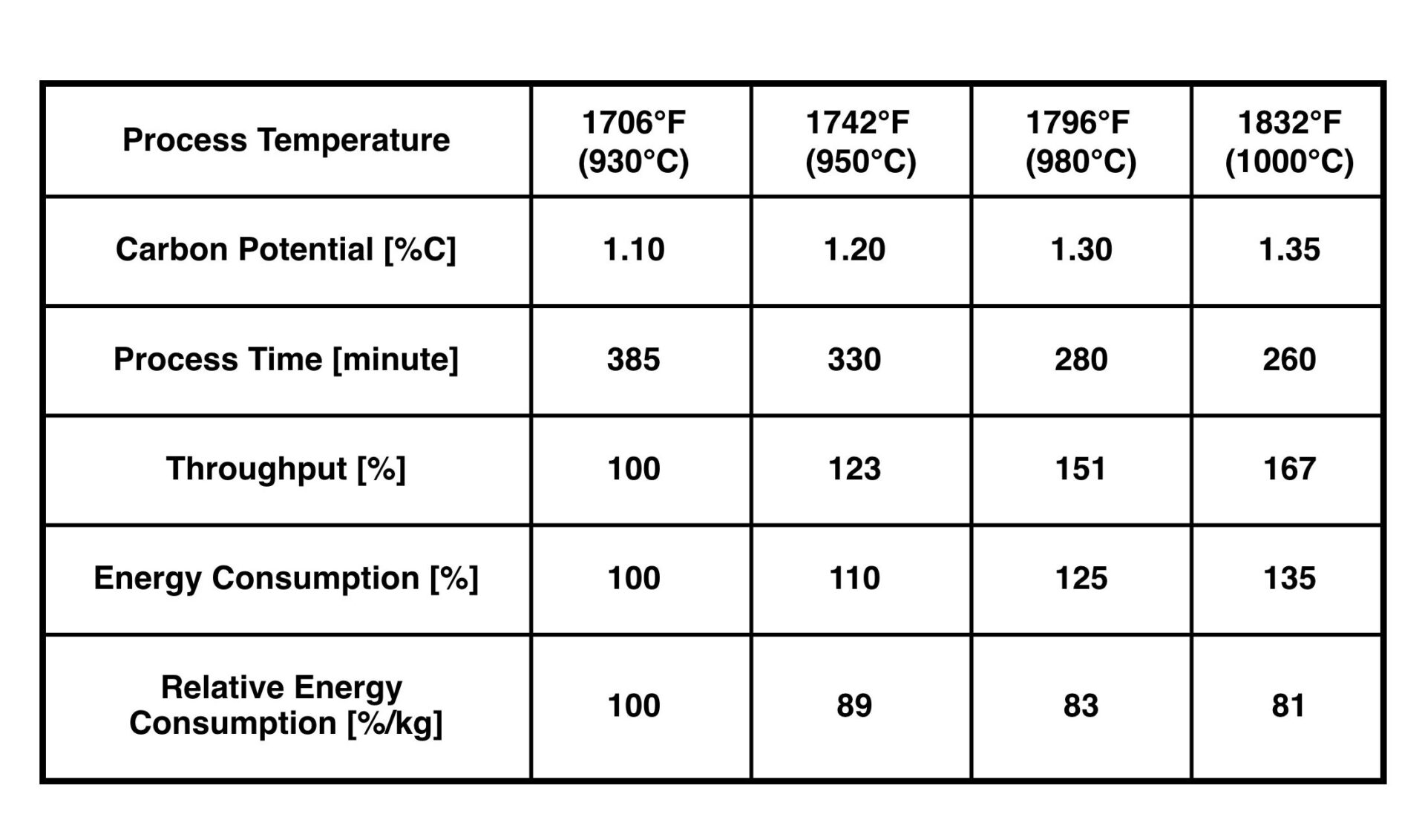

The high-temperature carburizing aspect should also be mentioned, although the term “high-temperature carburizing” is not fully accepted nor defined by international standards. As the temperature increases, the diffusion rate increases and the process time decreases. As shown in Table 1, the additional energy consumption is less than the increase in throughput that can be achieved. Therefore, the relative energy consumption per kg of material to be heat treated decreases as the process temperature increases.

There are three key issues to consider when running a high-temperature carburizing process:

- Steel grade: Fine-grain stabilized steels are required for direct hardening at temperatures of 1832°F (1000°C). Microalloying of Nb, Ti, and N as well as a favorable microstructure of the steels reduce the growth of austenite grains and allow carburizing temperatures up to 1922°F (1050°C) for several hours.

- Furnace design: In addition to the general aspects of the optimized furnace technology (e.g. heating capacity, insulation materials, and feedthroughs), failure-critical components must be considered separately in terms of wear and tear, whereby condition monitoring tools can support maintenance in this area.

- Distortion: This is always a concern, especially in the case of upright loading of thin-walled gear sections. As such, numerical simulations and/or experimental testing should be performed at the beginning to estimate possible changes in distortion and to take measures if necessary.

Heating System

Based on an energy balance that considers total energy losses, and preferably also temperature levels, it can be seen that the heating system plays a significant role. In addition to the obvious flue gas loss in the case of a gas-fired thermal processing furnace, the actual carbon footprint must be critically examined.

In the case of natural gas, the upstream process chain is often neglected in terms of CO2 emissions, but the differences in gas processing (which are directly linked to the reservoirs) and in gas transportation can be a significant factor.3 However, the analysis of energy resources in the case of electric heating systems is much more important. This results in specific CO2 emissions between 30–60 gCO2/kWh (renewable-based electricity mix) and 500–700 gCO2/kWh (coal-based electricity mix). Therefore, a general comparison between natural gas heating and electric heating systems in terms of carbon footprint is often misleading.

Nevertheless, in the case of gas heating, the aspect of combustion air preheating should be emphasized, as it has a significant influence on combustion efficiency. The technical possibilities in this area are well known and include both systems with central air preheating and decentralized concepts, where the individual burner and the heat exchanger form a single unit. Recuperator burners are often used in combination with radiant heating tubes (indirect heating) in the field of thermochemical heat treatment. With respect to oxy-fuel burners, it should also be noted that the formation of thermal NOx increases with increasing combustion temperature and temperature peaks. To avoid exceeding NOx emissions, staged combustion and so-called “flameless combustion” — characterized by special internal recirculation — and selective catalytic reduction (SCR) can be used. The latter secondary measure, together with selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR), has been state-of-the-art in power plant design for decades and has become widely known because of its use in the automotive sector. This system can also be adapted to single burners (Figure 2). In this way, NOx emissions can be reduced to 30 mg/Nm3 (5% reference oxygen), depending on the injection of aqueous urea solution, as long as the exhaust gas temperature is in the range of 392/482°F (200/250°C) to 752/842°F (400/450°C).4

Whether electric heating is a viable alternative depends on both the local electricity mix and the design of the heat treatment plant, which may limit the space available for the required heating capacity. In addition to these technical aspects, the security of supply and the energy cost trends must also be considered. Both of these factors are significantly influenced by the political environment. Figure 3 shows an example of the specific carbon footprint per kg of heat treated material with the significant losses based on the example of an integral quench furnace concept in the double-chamber and single-chamber variants electrically heated (E) and gas heated (G). The electric heating is based on a fossil fuel mix of 485 gCO2/kWh. Once again, it is clear that a general statement regarding CO2 emissions is not possible; rather, the boundary conditions must be critically examined.

Waste Heat Recovery — Strengths and Weaknesses of the System

Although improvements in the energy efficiency of heat treatment processes, equipment designs, and components are the basis for rational energy use, from an environmental perspective it is important to consider the total carbon footprint. An energy flow analysis of the heat treatment plant, including all auxiliary equipment, shows the total energy consumption and thus the potential savings. Quite often the temperature levels and time dependencies involved preclude direct heat recovery within the furnace system at an economically justifiable investment cost. In this case, cross-plant solutions should be sought, which require interdepartmental action but offer bigger potential.

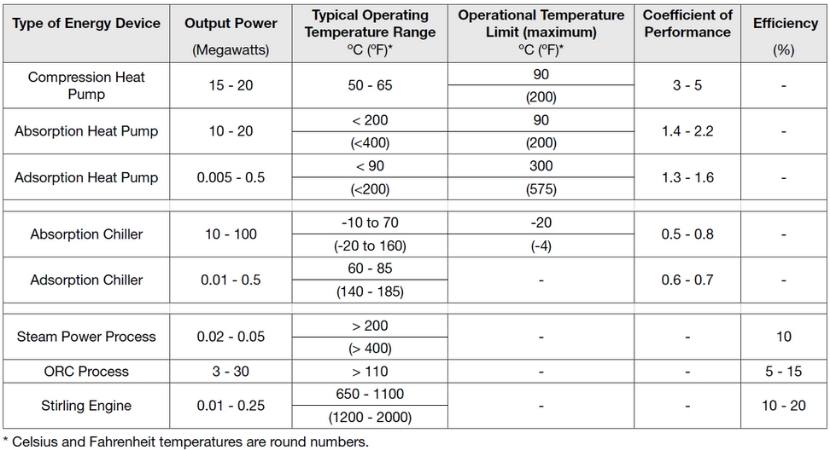

In addition to the classic methods of direct waste heat utilization using heat exchangers, also in combination with heat accumulators, indirect heat utilization can lower or raise the temperature level of the waste heat by using additional energy (chiller or heat pump) or convert the waste heat into electricity. The overview in Table 2 provides reference values in terms of performance class and temperature level for the alternative technologies listed.

Process Gas for Case Hardening

Case hardening — a thermochemical process consisting of carburizing and subsequent hardening — gives workpieces different microstructures across the cross-section, the key factor being high hardness/strength in the edge region. A distinction can be made between low pressure carburizing in vacuum systems and atmospheric carburizing at normal pressure. Both processes have different advantages and disadvantages, with atmospheric heat treatment being the dominant process.

Source: AICHELIN HOLDING GmbH

In terms of carbon footprint, atmospheric heat treatment has a weakness due to process gas consumption. To counteract this, the following aspects have to be considered: thermal utilization of the process gas — indirectly by means of heat exchangers or directly by lean gas combustion (downcycling); reprocessing of the process gas (recycling); reduction of the process gas consumption by optimized process control; and use of CO2-neutral media (avoidance). This article focuses on avoidance by optimizing process gas consumption and using of CO2-neutral media.

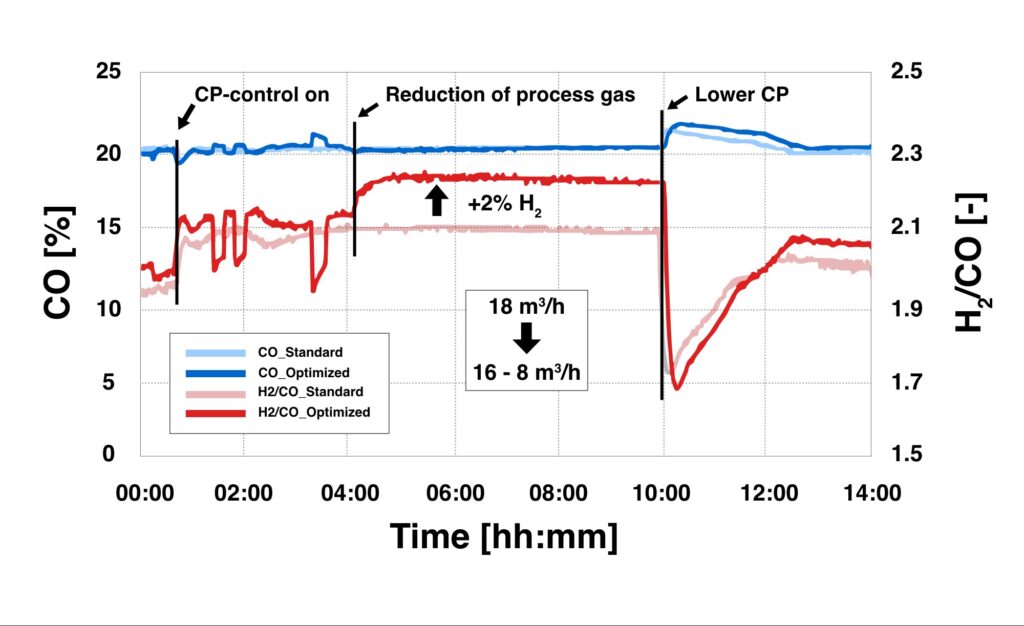

Typically, heat treatment operations are still run with constant process gas quantities based on the most unfavorable conditions. Based on the studies of Wyss, however, process control systems offer the possibility to adapt the actual process gas savings to the actual demand.7 In a study of an industrial chamber furnace, a 40% process gas savings was demonstrated for a selected carburizing process. In this heat treatment process with a case hardness depth of 2 mm, the previously used constant gas flow rate of 18 m3/h was reduced to 16 m3/h for the first process phase and further reduced to 8 m3/h after 3 hours. Figure 4 shows the analysis of the gas atmosphere, where an increase in the H2 concentration could be detected due to the reduction of the gas quantities. With respect to the heat treatment result, no significant difference in the carburizing result was observed despite this significant reduction in process gas volume (and the associated reduction in CO2 emissions). The differences in the carbon profiles are within the expected measurement uncertainty.

The carbon footprint of the process gas, however, must be fundamentally questioned. In the field of atmospheric gas carburizing, process gases based on Endothermic gas (which is produced by the catalytic reaction of natural gas or propane with air at 1832–1922°F/1000–1050°C) and nitrogen/methanol and methanol only systems have established themselves on a large scale. Methanol production is still mostly based on fossil fuels (natural gas or coal), the latter being used mainly in China. Although alternative CO2-neutral processes for partial substitution of natural gas — keywords being “power to gas” (P2G) or “synthetic natural gas” (SNG) — have already been successfully demonstrated in pilot plants, there are no signs of industrial penetration. Nevertheless, there is a definite industrial scale in the area of bio-methanol synthesis, though so far, purely economic considerations speak against it, as CO2 emissions are still not taken into account.

The question of the use of bio-methanol in atmospheric gas carburizing has been investigated in tests on an integral quench furnace system. A standard load of component parts with a CHD of 0.4 mm was used as a reference. Subsequently, the heat treatment process was repeated with identical process parameters using bio-methanol instead of the usual methanol based on fossil fuels. Both the laboratory analyses of the methanol samples and the measurements of the process gas atmosphere during the heat treatment process, as well as the evaluation of the sample parts with regard to the carbon profile during the carburizing process, showed no significant difference between the different types of methanol. Although this does not represent long-term experience, these results underscore the fundamental possibility of media substitution and the use of CO2-neutral methanol.

Conclusion

Facing the challenges of global warming — intensified by the economic pressure of rising energy costs — this article demonstrates the energy-saving potential in the field of heat treatment. In addition to already established solutions, the possibilities of the smart factory concept must also be integrated in this industrial sector. Thus, heat treatment comes a significant step closer to the goal of a CO2-neutral process in terms of Scopes 1, 2, and 3 regarding emissions under the given boundary conditions.

References

[1] Karl-Wilhelm Wegner, “Werkstoffentwicklung für Schmiedeteile im Automobilbau,” ATZ Automobiltechnische Zeitschrift 100, (1998): 918–927, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03223434.

[2] Wolfgang Bleck and Elvira Moeller, Steel Handbook (Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, 2018).

[3] Wolfgang Köppel, Charlotte Degünther, and Jakob Wachsmuth, “Assessment of upstream emissions from natural gas production in Germany,” Federal Environment Agency (January 2018): https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/bewertung-der-vorkettenemissionen-beider.

[4] Klaus Buchner and Johanes Uhlig, “Discussion on Energy Saving and Emission Reduction Technology of Heat Treatment Equipment,” Berg Huettenmaenn Monatsh 168 (2021): 109–113, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00501-023-01328-5.

[5] Technologie der Abwärmenutzung. Sächsische Energieagentur – SAENA GmbH, 2. Auflage, 2016.

[6] Brandstätter, R.: Industrielle Abwärmenutzung. Amt der OÖ Landesregierung, 1. Auflage, 109–113, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00501 02301328-5.

[7] U. Wyss, “Verbrauch an Trägergas bei der Gasaufkohlung,” HTM Journal of Heat Treatment Materials 38, no. 1 (1983): 4-9, https://doi.org/10.1515/htm-1983-380102.

About the Author

Klaus Buchner holds a doctorate and is the head of research and development at AICHELIN HOLDING GmbH. This article is based on Klaus Buchner’s article, “Reduktion des CO2-Fußabdrucks in der Wärmebehandlung” in Prozesswärme 01-2023 (pp. 42-45).

For more information: Klaus at klaus.buchner@aichelin.com.

This article content is used with the permission of heat processing, which published this article in 2023.