Heat Treat Today publisher and Heat Treat Radio host, Doug Glenn, sits down with Bill Jones, CEO of the Solar Atmosphere Group of Companies, to launch this new periodic feature called Heat Treat Legends where senior individuals in the North American heat treat market share their expertise and experience with those less senior.

Below, you can watch the video, listen to the podcast by clicking on the audio play button, or read an edited transcript.

The following transcript has been edited for your reading enjoyment.

Doug Glenn (DG): Welcome, everyone, to our inaugural episode of Heat Treat Legends. We're going to start with a true heat treat legend, a gentleman by the name of William Jones from Solar Atmospheres and Solar Manufacturing. We're going to talk to him about his life experiences and some of the things that we'd like to get his perspective on. So, Bill, first off, I just wanted to thank you for joining us. I appreciate you joining us for this episode of Heat Treat Radio.

Bill Jones (BJ): Thank you, very much, Doug, I appreciate the opportunity. As you know, I've had a long life, and to be a legend is something I never really expected. Most of us don't.

DG: Let's just talk a brief introduction — who you are, where you are right now, and what your role is in the companies that you own.

BJ: I've been a technocrat all my life. It started when I was very young, when I was about 7 or 8 years old. I've always been very technically oriented and technically driven. As a matter of fact, the various people that I have worked for have always complained about that, and they said, "You know, Bill, you're always interested in technology, and you're not interested in whether you're making or losing money. We don't want to hear about the technology, we want to see what's on the bottom line." That's sort of where I came from.

"I've been a technocrat all my life. It started when I was very young, when I was about 7 or 8 years old. I've always been very technically oriented and technically driven." - William Jones, CEO, Solar Atmospheres Group of Companies

After I graduated from college, I went to work for a small company, and we were involved in electromechanical things. A lot of our work was development work out of the DuPont company from their experimental station in Wilmington, Delaware, which was one of the premiere development centers in the country at the time. I don't think it's that way so much anymore, but, at the time, it really was a pyramid sort of place.

In my early days, I was introduced particularly into dew point analyzers. They had developed, what they called, a trace moisture analyzer which would measure down to about one or two parts per million. It was right out of the development laboratory and our company built it, and my boss, at that time, worked out to have a license to build the instrument. I ended up being the engineer in charge of putting the thing into production.

Like I say, at the time, (and we're talking about in the late 1950s or ‘60s), there was no real continuous recording of moisture or dew point. I'm talking about low, like down around -100 degrees Fahrenheit, a few parts/million. That was, sort of, a breakthrough. It was an interesting instrument. The instrument is still being built. So, I was very instrumental in that instrument.

That was my introduction into the technology, so to speak. Then, I went on and I became involved in optical pyrometers. As a matter of fact, I was going to bring with me, and I didn't, one of the early temperature optical pyrometers which was built by Leeds and Northrup. That was developed in the 1930s and it is still used today. It was the standard in the industry for many, many years. Anyway, that introduced me into the furnace industry, measuring temperatures with that instrument and then with an electronic optical pyrometer that was developed by another company. I learned all the problems with optical pyrometers respect to emissivity and all that sort of thing.

Those were my early years. I went to work, really, then, in about 1963 for Abar; I was the eighth employee with the company. That put me into the furnace business. Now, the Abar furnaces, at that time, were very high tech. They were designed to operate at temperatures of 4000 degrees Fahrenheit and up, above temperatures where you could really use thermocouples. That fit with my optical pyrometer experience; it was one of the reasons I went there. So, we were building these furnaces. We built them for the electronics industry, particularly for sintering of tantalum anodes, and so I had a very wide experience with that particular product. Then, it graduated into, and we got involved in, other technology. Particularly, we got involved with more normal, what I'll call, industrial processing, because this high temperature technology was either solid-state related, like with the tantalum capacitor or, at that time, with the development of the space launching and all that sort of thing.

With the changes in administration, we went away from space technology, to some extent, in the middle 60s, so it meant that we had this furnace technology and we had to put it to use. So then, we looked at industrial processes. We started to look at things like jet engine processing- processing parts for jet engines and all that sort of thing.

Those were my early years to get into this business. I went into the production aspect of the furnaces. And, of significant note, we built a number of furnaces for, what was, the atomic energy people, particularly at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. There was a bid that came out for a horizontal vacuum furnace, and it had a one-line drawing of a hot zone with a ring. (I shouldn't say a ring, we made it into a ring.) But it was this line drawing of a round hot zone with this part sitting in the center of it, which I really can't say too much about. But anyway, I didn't design that, but we had a couple of engineers that designed the hot zone

At that time, Abar was owned by a man by the name of Charlie Hill, and he overlooked the whole project. At the end of the day, after the thing was built, (but not turned on), they handed it over to me. I was like the equivalent of chief engineer for the company, so I had the task of starting that furnace up. It was a very interesting experience. It was, for the first time, when I really saw what that ring hot zone could do. I didn't really recognize all its advantages when we first put it online and started to test it, but we realized that we had something different. But, whenever you have something different, you don't always know what to do with it. That's about where we were. In a year or year and a half, we started to see the advantages of that hot zone.

I was instrumental in the development of the gas cooling system. The original system did not have any recirculation abilities, in other words, it would not quench; it was just static cooling. That whole thing of how to do that, I worked on, and after a lot of failures, I might say, we got it to work satisfactorily, and it has grown and grown and grown ever since.

There are other things about the furnace technology that I've had my fingers on and it's been a very pleasant experience, Doug. I could go on for the rest of our time talking about this, but I won't!

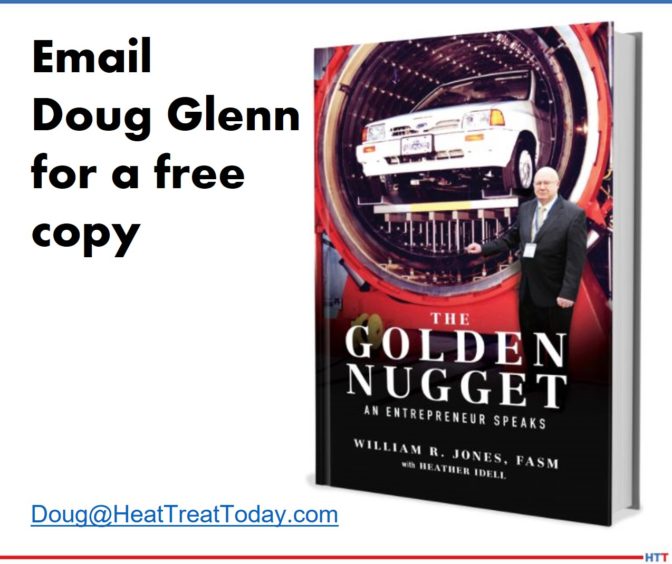

DG: That's good, that's good. At least it gives our listeners some sense of your background. And, I might mention Bill, besides being a technocrat, is also an author. He's authored a book called The Golden Nugget which came out in 2017. It goes into a lot of detail, mentioning a lot of the things you've mentioned here, and much, much more. If anybody is interested in getting a copy of that book, we'll put some information up at the end where people can either contact myself or you directly, Bill, and they can get a copy of that book.

BJ: Thanks, Doug, for the plug. Let me say this: Anyone who wants a copy of that book, I will be happy to send it to them at no charge, postage paid.

DG: Very good! You're being much more generous than I was going to be. I was going to say, feel free to call me, I'm going to charge you $50 for this book and you have to pay postage. ~chuckle~

Let's move on. Let me ask you a couple questions because people are going to be interested in knowing some of the life lessons that you've learned and things of that sort. When you look back on your career, which has been a good 50 years, I'm guessing, what would be the top one, two, even three accomplishments? When you're taking that 30,000-foot view and looking back, what do you see as far as major accomplishments?

BJ: The major accomplishment, obviously, is the development of the vacuum furnace, and that particular horizontal ring furnace. We didn't patent it at Abar, unfortunately. We should have, but we didn't know what we had, honestly, and then it got out into the field anyway and we couldn't patent it. Aside from that, that particular approach — that round furnace approach — has been duplicated by all our competitors around the world. That is a major accomplishment and it, really, has my name on it, which nobody will tell you, but that's okay.

DG: That's why we do these interviews. Just so people know, if you look behind you, Bill, on your screen, you've got a round cylinder furnace there. I think that's the type of thing you're talking about, there, with the flat band heating element.

"That was almost unheard of back then. Now it's been adopted all over the place, today. That's some of the major accomplishments."

BJ: Yes, round elements. It's a graphite hot zone which we developed. Our original hot zones at Abar were all metal. They were molybdenum and the elements were molybdenum, and the elements were all riveted together. Now, the advantage of graphite is that you don't have to rivet anything and, actually, part of my development was to be able to design the furnace, the elements anyway, so that they could be bolted together. Originally, the graphite heating elements, particularly the ones that were in the Ipsen furnace, and even predecessors before that, they were all tubular. They were put together not with threads, but they were put together, not like an erector set, but where you have pins and . . .

DG: Yes, couplers of some sort.

BJ: Yes, I'm not thinking of it right. But anyway, they were just pushed together, really, literally. They were troublesome; the joints loosened up. They were difficult. Cheap, yes. The graphite tube was very, very inexpensive. That was done at VFS (Vacuum Furnace Systems) when I established that company. We developed the round, and flat, thin, graphite heating elements which were bolted together with graphite screws and nuts. That was almost unheard of back then. Now it's been adopted all over the place, today. That's some of the major accomplishments.

DG: That is a major one.

BJ: Before you get off this, Doug, I selected the picture, that you noticed, on purpose. To heat treat something of that size and to bring it to full metallurgical properties, which they are (they are actually H-11 or H-13, I'm not sure which), but that's not exactly a forgiving alloy to heat treat and bring to full hardness of that size and weight. That's the advantage of our vacuum gas quenching over pressure. That furnace, or almost any one of ours, if you design it right, will do that job. I can tell you, in my early days getting into the heat-treating business, I tried to do big rolls like that and fell right on my nose.

This work was done out at our Hermitage plant which Bob Hill runs and it's an everyday thing, rolls like this and otherwise. That's why I put it up there.

DG: Right. That Hermitage plant is in western Pennsylvania and, yes, I've been in there and it's a great plant. You've got a lot of furnaces and much bigger furnaces than that, even.

I want to get to the human side of things. You've had a significant impact on a lot of people in the heat treat industry, me being one of them, to be quite frank. But I'm curious: When you were a young man getting involved in the industry, who were a couple of people who had a significant impact on you? Who helped you along?

BJ: I worked for a company up in Attleboro, Massachusetts for two years or so and they had developed a two-color optical pyrometer, and that's why I went to work for them. It had all sorts of problems because of emissivity — that’s a technical thing I don't want to get into — but the two-color pyrometer has not been well accepted because of that stumbling block.

Anyway, the owner of the company was Dr. George Bentley. I was with him for 2 years and I decided I wanted to leave the company. I was a field engineer for them in the mid-Atlantic operating out of Philadelphia. That company is in Boston. George called me on the phone, and he said, "Bill, I'd like to talk to you. I know you're leaving the company, but I want to have a time with you." I said, “ok.” This was back in the day when travel was not particularly great, so it took me most of the day to get up there. The next day I went in to see him about 9 or 9:30 in the morning.

I sat down with George and we both chitchatted for 15 or 20 minutes. The most important thing he said to me, at the end of the conversation, was, "Bill, I want to tell you something. I have observed you over the years and I can tell you, you are never going to be happy until you run and own your own business." I looked at him and that went right over the top of my head. That was never a thought, ever, in my mind. It didn't really have any impact for several years, but later I realized he was right. Until you're sitting in the top chair and until you're making the decisions of winning and losing, you don't know what it's all about. That was a prime moving event.

"[George said,] "Bill, I want to tell you something. I have observed you over the years and I can tell you, you are never going to be happy until you run and own your own business." I looked at him and that went right over the top of my head. That was never a thought, ever, in my mind. It didn't really have any impact for several years, but later I realized he was right." - William Jones, CEO, Solar Atmosphere Group of Companies

There were two people that were quite influential, and in a negative way: One was George Bodine from Lindberg, and the other was Sam Whalen from Aerobraze. Back towards the end of my Abar career, I had decided I wanted to go into the heat-treating business here in Philadelphia. My wife, Myrt, and I, independently, met with each one of them and their wives and we had dinner. And they said, "Ugh, Bill, you do not want to go into the Philadelphia area in the heat-treating business. It will never be successful." They both poured ice water down my back about going to business in the greater Philadelphia area in the heat-treating business. I cataloged that and, later, did it anyway. In a negative way, those two were very influential.

There were a lot of other people, too. Abe Willan at Pratt & Whitney. I had some people at General Electric that were very influential. There is a whole litany of people that I could thank for what they've done in my life and for what they've added to my career.

DG: Let's advance on here to the next question. I think this is always interesting to find out from somebody: One of those things if you knew at the beginning of your career, something you know now, what would it have been? Given your experience, what are the top two or three lessons that you've learned during your career that you think have been most helpful to you.

BJ: There are a lot of lessons learned. We, as practical people in the heat treat industry, tend to pooh-pooh education, not always, of course; I have metallurgists and PhD's working for us in the company. Anyway, my point is, those of us who are practical engineers and others who have come up through the ranks, like my son Roger and others, we tend to look at the practical aspects of heat treating.

What is the lesson learned from that? Well, education is really part of it. The basis of what we do comes from the field of chemistry. Metallurgy grew out of chemistry. If you don't have a decent educational background, then you don't know the basis of where we came from because that's the basis of where we're going. What I'm trying to say is: What is the lesson learned? The lesson learned is don't reinvent the wheel because the wheel does not have to be reinvented.

I think those of us in our younger years tend not to look over things like that. We tend to say, "Well, we're going to develop this and we're going to do it" come hell or high water and we end up falling on our nose. That's the point: take the time and effort to study what's been done and then go from there.

I would say, also, the other thing is to listen to what people in the field want and what their comments are about what you're trying to do. I think that's the most important lesson to share.

DG: Listen and learn, learn, and listen. Those are good, Bill. I appreciate that.

Are there any disciplines that you've developed, your work disciplines, your workday, or your work week? Are there any disciplines that you've developed over the years that have been helpful?

BJ: As I said, part of your discipline is your educational background. I don't want to emphasize that too much, but that's an important base to start from. My life has been a very workaday place. I have put all kinds of hours into my career and my work. I didn't do it to make money: I did it because, as I said in my early comments, I'm a technocrat. If I see something that needs to be developed, I work on it and I get to it.

I think work ethic, in our business, is very important. People who are successful, certainly in the heat-treating business and in almost any engineering discipline, have to put work into what they're doing. I'm talking about more than 40 hours a week; you're going to work 40-60 hours a week in order to accomplish. I know, Doug, you're doing that in what you do because I see the development of your magazine and all the things that you do; you're putting endless hours into the development of that thing.

The development of a business is like pushing a big cart up a hill. You're going to push, push, push, and get that cart up onto the top of the hill and you never stop pushing. You get to the top of the hill, and you think you're just going to relax and go from there, but you can't. There is always another mountain.

DG: Yes, another hill or portion of the hill. Let me ask you this, because it addresses the next question I wanted to ask you, and that was about work life balance. Have you had to struggle with that and how have you dealt with it?

BJ: Well, that's a very interesting comment. If my wife were here, she would tell you that I've dedicated my life to my work and I've abandoned her. That's not really quite true, except. . . . My wife, Myrt, and I have been married for more than 60 years and she is a wonderful helpmate. She has run the household since our early marriage and raised our children. I did too, but she was principal. The mother is the core of the family; the father is just a procreator, I guess. Getting your life in balance with work is always a challenge. I have been involved in church things for many years and one of our pastors once came to me with something he wanted me to do. His name was John Clark, and I said, "John, don't you realize how busy I am? To take this on is more than I really want to do." And he said to me, "Bill, don't you know, if you want something done, you go to a busy person?" So, I did it.

DG: I've got a two-part question for you, now. I'm sure over your career, you've had many ups and many downs. I want to start with one of the downs. What was one of the most difficult, trying times of your career? Then, after that, I want to know what was a highlight? What do you think was one of the pinnacles of your career?

BJ: I would have to say the most trying time in my career is that I've been involved in three lawsuits. If you get involved with lawyers and with the court, believe me, that is a trial. I was successful in each one of these and not being litigated to the point where I had to either pay or go to jail or what have you. But when you get involved with the law and with attorneys, number one, it becomes expensive, and number two, you're going to have a lot of sleepless nights over it. That's just bad.

Now, I have learned to avoid that, at all costs, if I can. Look, when you're in the business world, there are going to be challenging things — something doesn't work or whatever, and somebody is going to come back at you if they can. We live in a very litigious world, that's the problem.

People don't always live up to their obligations. I've learned it's best to do that. I'll give you an example: Just within the last two years, this was not a legal problem, but we had a furnace that was in the field. It had a deficiency in the furnace, and it was not easy to fix. So, I made the decision to completely bring that furnace back here to our main plant and to give the customer a brand-new furnace. By the way, we're talking about something that is $600,000. It's better to do that than it is to suffer the consequences.

Now, we brought that furnace back and I, personally, went over that with a fine-tooth comb to find out what in the world was wrong with it. We located the problems (it was in the chamber) and I had the chamber remachined on the front flange and that meant tearing the whole furnace apart and putting it back together again. It was only 2 years old. We completely fixed the problem, put it back online and then we resold it. We, obviously, lost money in the whole process, but our customer ended up happy with a new furnace, we satisfied him, and we went on from there. There is just a highlight of some of the issues that you can get into.

There are personal issues that sometimes hurt, but there is also a lot of gratification, too. A lot of people have appreciated the things that we've done, and I've appreciated more what they've done!

DG: Right: lawsuits and things of that sort are, obviously, kind of the low point. Can you nail down one, when you look back? What was the most enjoyable highlight of your career so far?

BJ: When I tested that first round hot zone, I did it by myself at night in a plant where I was the only one there. We had a big sight glass in the front of the furnace, and I could see the entire hot zone, the heating element, the heat shield, the ring and so forth, and I was able to measure the temperature and it was a WOW. This thing works! That was a highlight.

DG: If I had answered this question for you, I would have thought you would have said something like starting your company and building two furnace manufacturing companies. You've got four successful commercial heat treat companies, as well. I would have thought that a lot of the accomplishments along those lines would have been highlights for you.

BJ: You're right. And, along those lines, the car bottom furnaces that we've built, particularly the ones that are at Hermitage in western Pennsylvania, are a highlight. The very first one is a chapter on how that furnace came to be.

Anyway, it was designed and built by a group of engineers. I was on top of that. We met weekly during the design phase. We didn't put it together completely here at Souderton, we put it together to know that it was vacuum tight and so forth, then we took the furnace all apart, shipped it to Hermitage, put it all back together again and we ran test cycles on that furnace, empty. It did everything that we wanted it to empty, but that's not putting a workload in it.

One of the reasons for building that furnace was to process these big titanium coils that were very heavy. So, we put six of them into the furnace. I said, "I want to process six of these coils," and we had like a 20-25 thousand-pound workload of titanium in the furnace worth a lot of money, we're talking about probably a million dollars of work in the furnace. At the time, Bob Hill said, "Bill, you're not going to run the final product first. I think we should make a run with just some scrap steel that we have around." I said, "No, Bob. I am thoroughly convinced this furnace is going to work and work right. Let's put the coils in there and run it." And we did. You know what? It was 100% right. It worked. It was a big success. There have been other things, too, but that was one of the highlights.

DG: Let me ask a couple final questions. Based on what you're seeing going on today in the world, in the industry, wherever you want to take this one, Bill, is there any advice or wisdom that you'd give to today's up-and-coming heat treat industry people?

"I think, from my prior comments you'll get this. There is nothing that beats hard work and dedication to what you're trying to do." - William Jones, CEO, Solar Atmospheres Group of Companies

BJ: Yes, I would say this and I think, from my prior comments, you'll get this: There is nothing that beats hard work and dedication to what you're trying to do. So, what would I say to a young person, let's say, somebody that is in college, and they want to think about their career?

First, you want to do something that you're happy doing. You don't want to work at something that you're unhappy at. If you're unhappy, get out of it and do something else. You want to be happy at your job. That's number one.

Then, you must be properly prepared for it. You must have enough education to go forward. If you're going to be a writer or something involved in marketing, you must have some experience and training in that field. I have a marketing person sitting in the room with me, so I have to say that. She's a young person, so I can talk to her. That's the kind of advice I would give to a young person. You want to be dedicated, you want to be happy, and you want to work at it. You have to work at it. You're not going to have it handed to you. At least here, in our economy, in the United States, which we have a wonderful opportunity, the only opportunity in the world is, really, here in the United States.

DG: Last question. This is a question that I'm curious about. The group of companies that you've established — Solar Manufacturing, Magnetic Specialties, all the Solar Atmosphere companies — are all US-based, family-owned and a single business, separate entities but all owned by you and Myrt.

BJ: That's right. I can tell you that 100% of our companies are owned by Myrt and I. We have no other shareholders or stockholders. Originally, at VFS, I did. That long story is in my book, but no, today, 100% Myrt and I own the businesses.

Of course, this is a two-edged sword. If all these businesses were up and running and they are all successful, like they are today, and if I were 40 years old, I would have another, possibly, 40 years to look forward to and to operate these businesses. Now, at my age, I'm over 80 years old, so how many years do I have ahead of me? You can count them on one hand if that. We don't know.

DG: I was going to say, let's not put a limit on that, the Lord knows.

BJ: That's right, exactly. That's exactly what I was going to say. You and I understand that all too well. It's all in the Lord's hands. Myrt and I both feel that we've got a few years ahead of us, but we just don't know. Someone else commented to me, they said, "Well, your other competitors, and so forth, have been bought and sold by other businesses and you have not." I've looked at these companies that have been bought. Somebody made some money when they were sold, but I can tell you the employees certainly didn't make out on that. Any employee that's involved, particularly if you're at the higher end of the company, your life is in jeopardy because you don't know what the new owners are going to do. Half the time, within two years, you're going to be out on the street and all the hard work that you've put into the company is going to go down the drain.

DG: Right. This is getting to the core of the question that I wanted to ask, and that was that you've got successful companies going on, their family owned, they're going into a third generation of Jones, who is going to be helping to run the business and things of that sort. So many of your competitors, whether they be furnace manufacturers or actual commercial heat treaters, have either been sold, consolidated into bigger companies or, on the furnace side of things, many of them are now owned by international companies, companies outside of the United States.

My question to you, specifically, is why do you think it is that Solar has been one of the few companies that has been successful in maintaining a privately-owned, family-owned business where others haven't?

BJ: We are a family-owned company and the fact that we have not been bought or sold, (and we’ve had the opportunity, but I didn't want any part of it), what's the bottom line? Why? Well, it's very simple: Money is not a driving factor in my life or in my wife's life. Money is not it. You know, the old saying is, when you go to the grave, there's not going to be a U-Haul behind you. You're going there with what you came with, which is nothing. My father once said, "Money doesn't really mean anything except that you can live a little more comfortably," and he was right about that. But, at this point in our lives, my wife and I are comfortable enough, and we certainly don't need to add on and on and on to our personal wealth.

I guess, to put it in simple terms, there is no reason for us to sell the company. If we can turn it over to our operating people who now are running it, and if they can do it successfully, God bless them, and what I and my wife, Myrt, have started can continue. And, you're right – in the room with me is Trevor, my grandson, and he is the third generation. Behind him is another Jones, his name is Cole, who is now 14 years old. He's not working for the company; I don't know what he's going to do. Trevor worked in this company since he was 16 years old, maybe a little bit earlier. He's saying, “Yes, I think you're right” His whole life, like mine, has been dedicated to this business. I don't know if that answers your question.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Jamie Jones, a grandson of Bill Jones, brother of Trevor Jones, and the father of Cole Jones, is also one of the key third generation leaders. Jamie is president of Solar Atmospheres in Souderton and Trevor leads Solar Manufacturing in Sellersville.

DG: Yes, I think it does. I think your quick answer- you're not a money driven person says a lot.

Well, Bill, that's it. I really appreciate the time you've taken to spend with us. I want to encourage people in the industry to make sure that they pick up a copy of your book, The Golden Nugget - An Entrepreneur Speaks, by William Jones and Heather Idell. It's worth reading. Bill, thank you very much. I really appreciate the time you spent with us, today, and congratulations on being a heat treat legend.

BJ: Thank you very much. The Lord's blessed us in that respect, Doug, and you.

DG: Yes. Thank you very much.

BJ: You're welcome. Bye-bye.

To find other Heat Treat Radio episodes, go to www.heattreattoday.com/radio and look in the list of Heat Treat Radio episodes listed.