Heat Treat Radio host, Doug Glenn, talks with Thomas Wingens, president of WINGENS LLC – International Industry Consultancy, about the growing popularity of ferritic nitrocarburizing (FNC) and whom this process would benefit most. Listen and learn all about FNC and how it might be a help to your production process.

Heat Treat Radio host, Doug Glenn, talks with Thomas Wingens, president of WINGENS LLC – International Industry Consultancy, about the growing popularity of ferritic nitrocarburizing (FNC) and whom this process would benefit most. Listen and learn all about FNC and how it might be a help to your production process.

To find the previous episodes in this series, go to www.heattreattoday.com/radio.

Below, you can listen to the podcast by clicking on the audio play button or read the edited transcript.

The following transcript has been edited for your reading enjoyment.

Doug Glenn (DG): We want to welcome Mr. Thomas Wingens who is from WINGENS LLC – International Industry Consultancy. Thomas is no stranger to Heat Treat Radio. Thomas, you’ve been here before and, in fact, you’ve got one of the more popular Heat Treat Radio (as far as downloads). It’s one of the ones we did several years ago, actually, on megatrends in the heat treat industry. But, anyhow, Thomas, welcome back to Heat Treat Radio.

Thomas Wingens (TW): Thankful to be back, Doug.

DG: If you don’t mind, Thomas, let’s start off very briefly and give the listeners a brief idea of your history and your current activities in the heat treat industry.

TW: My name is Thomas Wingens. I am an independent consultant to the heat treat industry for 10 years now. I have been in the heat treat industry for over 30 years. As a matter of fact, my parents actually had a heat treat shop and I was born and raised above the shop. We had various heat treat processes in our shop. Vacuum heat treating we started in the early ’70s, but also atmosphere heat treating and nitriding.

Nitriding – I am also familiar with this, now for over 30 years. I work with different companies and manufacturers on the one hand, but also other commercial heat treat shops (like Bodycote and Ipsen). I am a metallurgist by trade. I studied material science.

Today, I live in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania with my family (not far away from you, Doug), and we really enjoy it here.

DG: It’s very obvious you’ve got heat treat in your blood. You were born and raised in Germany, but you’ve been here in the States for quite a few years now. You’re well acquainted, and I think this is important, with not only the European technology that we’re going to talk about today – which is ferritic nitrocarburizing – but you’re also familiar with the U.S. market. It gives you a good “in” in both of those markets and so a good perspective to share with our listeners.

This episode is basically going to just cover FNC, ferritic nitrocarburizing. We want to start at the basic level and work down through a few questions for anyone interested in what it is, how to do it, and that type of thing. If you don’t mind, FNC 101.

What is ferritic nitrocarburizing?

TW: It is aligned with carburizing and nitriding into fusion treatment. It is thermal process diffusion, not a coating. As it is ferritic, it means it is not austenitic. So, we’re not heating parts as high as we would do with carburizing or carbonitriding, which is more the range of 950 Celsius; nitriding in general is operated in a temperature range of 500 Celsius range and ferritic nitrocarburizing is in the 560 – 590 Celsius range. We are not austenitic, and that makes a huge difference, especially when it comes to distortion. We are treating with FNC parts which are ready to build in. It is the final step, very often. That is a huge difference. We can do this because we do not experience any distortion.

Source: Paulo

DG: So, you’re doing it at a lower temperature range, we don’t have to worry about distortion and things of that sort, and it is, more or less, the final step.

TW: It is. Like nitriding, the nitriding is taking place in the 500 – 540 Celsius, and usually the nitriding takes longer; it is up to 90 hours very often, so deep case nitriding is very popular for some applications. The rise and the popularity of FNC is that we can achieve results very fast. First of all, we are at elevated temperature versus nitriding as we are operating at 580 – 590 degrees Celsius.

But there is also the carbon content. The additional carbon, in conjunction with the nitrogen, also accelerates the diffusion. We are achieving faster diffusion layers with FNC than with nitriding. So, shorter cycle times means lower costs and faster turnaround. Instead of having 24 or 90 hours cycle times, we often have 4-6 hours.

DG: Let’s do the comparisons again of the processes. You’ve got nitriding which is probably the lowest temperature process, but it’s a much longer cycle. If we’re moving up in temperature, probably ferritic nitrocarburizing would be next. It’s going to be a much shorter cycle because you’ve got the addition of carbon as well, which is helping diffusion into the metals. Then you’ve got nitrocarburizing or carburizing, both at much higher temperatures. In fact, when you get to carburizing, you need to worry about distortion, I would assume, correct?

TW: Exactly. That makes a big difference because it is not the final step after carburizing or carbonitriding which is taking place at 950 degrees Celsius, or, if you go into a vacuum furnace with LPC, you can go even higher (up to 1000 Celsius). Nevertheless, you’re in the austenitic field. When your part is cooler when being quenched, you transform from austenitic to martensitic, and then you get distortion associated with quenching and the ensuing transformation. That means you need to grind the parts to have finished parts. That’s not the case with nitriding or nitrocarburizing or FNC.

DG: As an example, can you list off some parts that typically go under FNC? What are people typically ferritic nitrocarburizing? What types of parts?

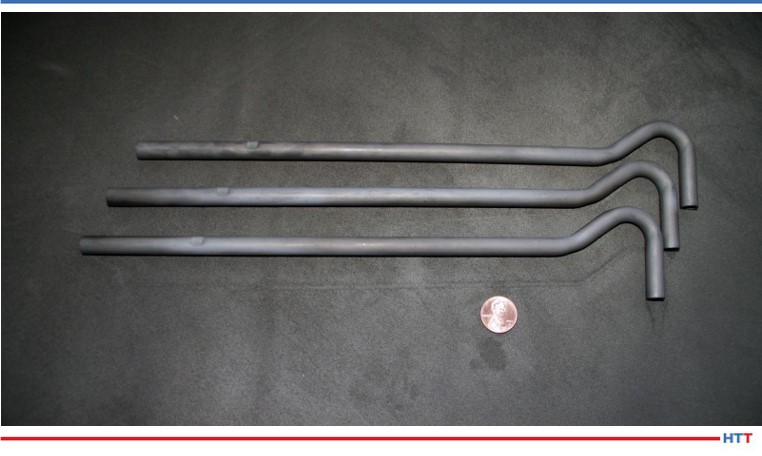

TW: Due to the fact that we have a couple of micron layer only, (that means you don’t have huge parts, for the most part), you are doing .3mm up to 3 or 6mm for deep case for windmill gears. With the size of the part, usually the surface treatment layer is growing as well, so it really depends on the wear.

Nitriding certainly can be applied on large parts and it is done on very large parts, meaning 7 meter long extrusion screws and such; but it is because of the wear. The work technique you have on a very unique surface layer with nitriding and nitrocarburizing is formed from friction. When you have chemical wear, when you have fatigue wear, you get a couple of things. One of them is you have compressive stresses that are holding up to some degree of fatigue, and then you have, of course, a high surface hardness of 1200 vickers. You have a very high surface hardness and then if you have galling or pitting where metal on metal is wearing. The nitriding layer is very supportive here. But also, the chemical resistance is a very big factor.

A big part of the success of FNC is the combination with post oxidation. That is a big part because the combination of ferritic nitrocarburizing with post oxidation leads not only to a mechanical strong surface with compressive stresses, it also has a very high corrosion resistance. That combination is a wonder combination for several automotive parts. A lot of components have been hard chrome plated in the past. So you have several ball pivots, ball joints, in the car. When you have an older car with chrome plated ball pivots, you maybe have heard an itchy noise, when the car makes a noise when you go over a curb or when you go up and down. That is very often due to the fact that these ball joint pivots are corroded and were chrome plated. That is a huge application. That became the standard in the automotive industry. Every ball joint is now FNC and post oxidized.

The other application that you see a lot is if you have a pneumatic trunk lift piston. The piston, you remember, has been hard chrome plated so that you have the chrome finish. You will see in a newer car, in the front hood, you have a gas piston that is FNC treated and post oxidized. Everything that is exposed to corrosion, which are so many parts on the automobile, even the light building of the body. This is something to mention.

[blockquote author=”Thomas Wingens, WINGENS LLC – International Industry Consultancy” style=”1″]A big part of the success of FNC is the combination with post oxidation. That is a big part because the combination of ferritic nitrocarburizing with post oxidation leads not only to a mechanical strong surface with compressive stresses, it also has a very high corrosion resistance. [/blockquote]

All of these components I’m mentioning here are body parts predominantly and have nothing to do with electrification or with internal combustion drive trains. They are not impacted by that, so we will not see any change here in the future. A lot of under body components, where there is stone chipping and all the corrosion, people are tending to use FNC and black oxide because they can make it on thinner sheet metal part with compressive stresses so they have higher strength built in and they have the corrosion protection on top of it. It’s a good combination. And, of course, it’s virtually distortion free. You may see that on some parts, due to very high compressive stresses, there is a buildup on the corners, but other than that, it is virtually distortion free and that’s a big, big plus of FNC.

DG: That explains why it is growing in popularity. I think that’s one thing you and I talked about earlier; there seems to be within the last, I don’t know, five years for sure, it seems like you’re hearing a lot more about FNC than you used to hear about. Nitriding is still popular and carburizing is still popular, but you’re hearing a lot more about FNC, primarily because of the things you said. Are there any other reasons, or is that primarily it? Cost savings and good qualities.

TW: If you look back, Doug, in the early days, in the beginning of the early nineties, I was running our nitriding department in our heat treat shop, and I had this little shaker bottle where it can determine the disassociation of ammonia and that determined the nitrogen potential. The outcome was mediocre, to tell you the truth. We did not clean the parts, we just put ammonia on it, and we had no way of controlling it other than the time and the temperature, so the outcome was a big variation. That’s why it was limited. You could not find anything in the aerospace industry. Nitriding was not accepted in aerospace at all. Even in the automotive industry in the nineties, you did not find anything nitrided. It was only used on tooling applications, and such.

But with the controls you have today, with the probes and sensors, you can determine everything, and you can see exactly what’s going on. That has been a big factor. There is the reproducibility of the layer you achieve and that is only possible with the good controls that you have and a better understanding of the process.

And, it is very important to mention, the cleaning of the surface. There is no other heat treat process which benefits from good cleaning than nitriding and nitrocarburizing or FNC. That makes a huge difference because you’re operating at a lower temperature and you don’t necessarily get rid of all the impurities and the ammonia gas, which, speaking of the process, really relies on the surface cracking of the material to dissociate in. We have seen a huge impact if parts are not cleaned well on the different surface layers of FNC where we have missed the wide layer in total and such, so that is a big difference.

DG: And the cleaning, I assume, besides just particles, I assume we’re talking about removal of grease and chemicals and things of that sort so that there can be good diffusion.

TW: Exactly. The surface has to be active. The chips and the dirt to remove, that’s the easy part, but you have, sometimes, salts and residue from cutting and forming, especially the forming agents, sulfur phosphate, which are very hard to remove, especially for parts that are often FNC treated, like deep drawn parts or cheap metal components that are cut and there we see a big difference if they’re not cleaned well.

DG: Run our listeners through a typical FNC process. How does it happen?

TW: I think it’s important to mention, as we haven’t done it yet, that we have three different processes. We have salt bath nitriding or nitrocarburizing, gas, and plasma. Each process has pros and cons.

Source: Bluewater Thermal Solutions website

The salt, there is a [cleaning] process or…QPQ, there are a lot of names out there for salt bath nitrocarburizing. It is wonderful in that you just dunk it in, it’s quick. The problem is the cyanide salts. You have to carry it over, you have to clean it, you have to appropriately handle it, store it, and not everyone likes to do that. Other than that, you have wonderful mechanical results with salt bath nitrocarburizing.

And then there is the plasma process. The plasma is excellent for certain geometries, not so much for bulk. You can place the parts in the furnace; it’s wonderfully clean and environmentally friendly. Everything is good. The problem is twofold: it is hard with bulk loads, it’s not as flexible on various parts and the other is with the post-oxidation, you cannot do it with plasma because it technically doesn’t work, so you need the… of gas nitriding in the plasma furnace to have the oxidizing part of the process, if you wish to go that route.

Having that said, the most widely accepted process is gas nitriding and gas nitrocarburizing. Everyone knows that in pit furnaces this is one of the arrangements. You put the parts in the furnace either vertically pit or modern now love horizontal arrangements, so if there is a loader you just have a batch. Then you either purge with nitrogen gas or with a newer equipment that have a vacuum pump, so they have a vacuum purge system and instead of flushing with a lot of gas that draw a vacuum, they heat up the load and the convection to 580–590 degrees Celsius. That can be done with so called “pre-oxidation process.”

Some people, especially if you have higher alloy chrome 4140 – “chrome alloyed” steels – they’re better to nitride if they are pre-oxidized on the way up. Other than that, you would nitrocarburize ammonia gas, when you do gas nitriding, in conjunction with either endogas or CO2 gas. Both, in combination, over a cycle time of 1 hour to 4 hours, soaking time and process time, and then you cool down with gas. Not with the ammonia. A lot of people make that mistake. They heat up with ammonia or maybe even cool down with ammonia, but that is not correct. Depending on, of course, what you’re trying to achieve, the best way is to flush it out because you have different disassociation processes going onto the surface and you have whatsoever surface combination nitrides if you don’t do it properly.

DG: Are we gas cooling with nitrogen then?

TW: You’re better off cooling with nitrogen. Or you go interrupted cooling and then you oxidize on your way down, then you have this so called post oxidation. You cool down to 300 – 350 C, and you have an FEO to layer which is dense, which is important. You don’t want to have a flaky one or rough one, you want to have a dense oxidized layer as a surface and then you continue to cool. That is basically the recipe of FNC.

DG: I didn’t ask you before, and I should ask you: metals with which you can nitride or FNC, are they basically all steels? Are there some steels you can’t do it with? How about aluminum? Titanium? What can you do FNC with and what can’t you do it with?

TW: I would say that nitriding is applied to a much broader spectrum of steels and even other alloys, let’s say. People even do titanium and nickel alloys and try to put in nitrogen surface, calling it nitriding. That is much broader. FNC with nitrocarburizing is typically done with low carbon steels or carbon steels rather than high alloy steels. That is why we have sheet metal parts very often. So, low carbon or plain carbon steels.

DG: And that’s maybe another reason, Thomas, why it’s become a more favorable process, right? You can get some of the mechanical properties out with less expensive materials. Is that safe to say?

TW: Yes, that can be part of it. But you should have a pre-hardened material, that’s important. You need some carbon content in to have some hardness which sustains the high hardness of the surface. It’s all prehard metals, for the most part. Not necessary, but it certainly helps if you have some strength in the sub-strength which is supporting the hard layer. It truly depends on your application. But, you’re right: you can save on the materials to some degree and still get the mechanical properties that you’re looking for, especially in combination with the carbon.

DG: Two final questions that maybe will help some of our listeners who are thinking about moving into the FNC direction. The first question is, Who are the companies, and I know we can’t be exhaustive here, but who are some of the companies that actually manufacture this type of equipment that they could speak to? And secondly, What are some of the things that companies ought to be asking themselves before they decide to go down the FNC rabbit trail, if you will?

So, first a list of companies if you have them. We’ll try to be more exhaustive in our transcript of this. If we miss any here, we’ll list them in the transcript. But if you could rattle off a few that you’re comfortable with.

TW: There are the plasma people, that is RÜBIG GmbH & Co KG and Eltropuls and PlaTeG. On the salt side, you have HEF Group, Degussa, and Kolene. On the gas nitriding, you have Lindberg/MPH and Surface Combustion. On the horizontal, very recently over the last 20 years, a very popular design is a horizontal vacuum perch retort nitriding and nitrocarburizing furnaces. There you seen Ipsen, a German company called KGO, but also you have SECO/WARWICK with some proprietary designs (zero flow is also a good concept), and lately Gasbarre came into this business and Solar as well; they have the vacuum purge nitriding firms.

DG: I want to back up a little. On the salt bath companies you mentioned several, I also know Ajax Electric, also Upton Industries. I don’t know if they do FNC units, but I’m assuming that they do. There are a lot of other companies.

TW: Salt bath is unique to salt. There are only two, or three maybe, companies left in the world who supply these salts. It’s more popular in Japan, by the way. Anyway, it’s not as big as the gas process.

DG: So, I’m a company thinking about maybe converting from some other surface hardening process over to FNC. What kind of questions should I be asking myself?

DG: So, I’m a company thinking about maybe converting from some other surface hardening process over to FNC. What kind of questions should I be asking myself?

TW: It all starts, of course, with the product and the application. Then you need to understand the wear and the corrosion methods. That has to be well understood. If that leads to FNC being the most suitable solution for this application, you need to understand the details of how you want to build up the surface layer, the thickness of your diffusion layer, the compound layer, the wide layer on the top and if you want to do post oxidation, so you will also need to do the oxide layer, which by the way, very often needs to be polished at the end, as well, to increase corrosion resistance. These kinetics need to be well understood and the wear and what you want to achieve with this.

Then, of course, you have to see the design. If you have sheet metal components which are cut, the cutting corner usually receives a higher layer and then the corners themselves that built up due to stresses, so there are a couple of minor things that need to have attention. Then, of course, you need to have an expert who really refines the process, and that has to be done in conjunction with good controls. There are two or three companies in the market. UPC is one of them. Oh, I forgot to mention Nitrex, a big brand.

DG: UPC is part of Nitrex, but they also do the process.

TW: Right. Very important. Somebody who really understands the nitriding and the control part of it. UPC Marathon, they have very good controls. SSI also has the probes. There is STANGE in Germany as well. You have two or three companies which have good knowledge in the controls and the probes and how to control this nitriding process. Then you can build up your desired layer system. In the layers, you have a diffusion, then you have a compound, a white layer, and then maybe you have an oxide layer on top and that needs to be well understood. And, of course, as mentioned before, it is essential to have parts cleaned thoroughly and if you maybe need a polishing afterwards. Then, of course, how you put them in the furnace (placement) so that the gas can uniformly penetrate the parts. These are the essential things.

DG: There you have it, folks. That’s FNC 101. Those are the basics in ferritic nitrocarburizing from Thomas Wingens. Thank you, Thomas. I appreciate it very much. I know that if people have questions, you, specifically, would be more than happy to help them out. The company again is WINGENS LLC – International Industry Consultancy. Thomas, www.wingens.com.

TW: That’s it!

Doug Glenn, Heat Treat Today publisher and Heat Treat Radio host.

To find other Heat Treat Radio episodes, go to www.heattreattoday.com/radio.