Heat Treat Radio host, Doug Glenn, talks with Greg Steiger of Idemitsu Lubricants America Corp. about the causes and dangers of water in your quench tank, how to know if you have too much, and what to do about it if you do. This highly-informative episode is a must watch/listen for those who oil quench.

Heat Treat Radio host, Doug Glenn, talks with Greg Steiger of Idemitsu Lubricants America Corp. about the causes and dangers of water in your quench tank, how to know if you have too much, and what to do about it if you do. This highly-informative episode is a must watch/listen for those who oil quench.

Below, you can watch the video, listen to the podcast by clicking on the audio play button, or read an edited transcript.

The following transcript has been edited for your reading enjoyment.

Doug Glenn (DG): Greg, welcome to Heat Treat Radio. This is the first time you’ve been on, and I know we’ve talked about doing this for quite a while, so, welcome!

Greg Steiger (GS): Thank you, it’s my pleasure.

DG: I asked the question, before we hit the record button, but I think we need to ask the question again: The big white flag in the background with the W, you need to tell us about that.

GS: That’s the flag that they fly outside of Wrigley Field every time the Cubs win. They’ve been doing this for almost a century so that way when they were only playing day baseball and you could come home on the L, you could see if the Cubs won or lost without looking at a box score.

DG: That’s great! Now, you are not in the Chicago area, are you?

GS: No, I’m in the Columbia, SC area, but I was born and raised in the Chicago area.

DG: So, you’re a Cubby fan.

GS: I am.

DG: Being from Pittsburgh, I forgive you for that.

So, Greg, first thing, can you give our listeners and viewers a brief background about yourself and then we’ll jump into the water topic, so to speak?

GS: Sure. I got into this industry when I graduated from college in 1984 as a formulating chemist. I eventually worked my way into, what we call, customer service or tech service, where I’d go out and visit customers, run product trials if customers had problems. I worked my way into laboratory management and eventually sales and marketing. I’ve been at Idemitsu for the past 9 years. Since I’ve been at Idemitsu, I’ve earned a master’s degree in materials engineering, and I’ve learned a lot about heat treat and it’s really become my passion. I am currently the market segment leader for heat treat products for Idemitsu.

DG: I should congratulate you on that degree, by the way. I know a year or so ago, you were still working on that, so that’s great!

DG: I should congratulate you on that degree, by the way. I know a year or so ago, you were still working on that, so that’s great!

GS: May 6th I graduate.

DG: Tell us, just briefly, for those who might not know about Idemitsu. We can see it on your shirt but tell us about them a little bit, so people have a sense.

GS: Idemitsu is a very well-kept secret here in the U.S. They are actually the 8th largest oil company in the world. We are a Japanese owned company. There is about an 85-90% chance that no matter what vehicle you drive, you’ve got some of our fluids in it. The largest market share is the automotive air conditioning compressor market, but basically, if you drive a Honda, Mazda, Subaru, or Toyota, it left the plant with our engine oils, our transmission fluids in it at the factory.

When it comes to quench oils on the industrial side, Idemitsu is actually the 2nd largest quench oil provider in the world. Even though we’re Japanese, all of our heat products, in general, are made and blended here in the U.S.; we don’t import anything from Japan for our heat treat products.

DG: Very interesting. So, a big company — somebody worth paying attention to, I think is the point. You’re right — it’s the best kept secret. We’re trying to work to not make it so secret.

GS: We’re doing what we can, Doug.

DG: This next question I’m going to ask you is very, very basic and most people listening I’m sure will know this but there may be some who don’t: Why is water in quench oil a problem?

GS: A little bit of water is not a problem because it will happen naturally through condensation, but when you start to get too much water in there, a couple of things happen. Our research has shown that basically about 200-250 ppm water, you start to get uneven cooling.

A quench oil is not a completely homogenous fluid; it’s possible to have water in one area of the tank and no water in the other so you can get different cooling speeds in different areas of the tank. When you start getting up to large amounts of water, somewhere around 750 ppm to over 1000 ppm, it becomes a safety issue. What happens is — when water turns into steam, it actually expands. Most things when they get warmer, they contract, but water is the opposite — it expands. It expands 1600 times at boiling and the hotter the steam gets, the more it expands.

"A little bit of water is not a problem because it will happen naturally through condensation, but when you start to get too much water in there, a couple of things happen. Our research has shown that basically about 200-250 ppm water, you start to get uneven cooling."

Think of it: If you have a gallon of water in a 3,000-gallon quench tank, when you boil that water, it turns into 1600 gallons of steam, and it’s got nowhere to go but up and out of the quench oil and it’s going to carry the quench oil with it onto flame curtains, other hotspots on the furnace, and that’s why it becomes so dangerous.

DG: It’s really the risk of explosion, in a sense. That’s basically what we’re talking about. I could be wrong, but my gut feeling is that a vast majority of quench fires are started because of water that happened or simply the product not getting down into the quench fast enough. But a lot of it is caused by carrying water in with the part.

GS: Not necessarily on the part but being in the oil itself through various means. As I said, it happens naturally every time you heat an oil up and you cool it down, you get condensation, but that’s usually only a few parts per million, and every time you drop a load in, you’re driving that water off.

DG: Right. Raising up the temperature and therefore boiling off the water.

GS: Right.

DG: This is a follow-up question into what we were just talking about, and maybe we’ve answered it: Where does the water come from? Is it typically just condensation or what are the top ways water gets into the tank?

GS: Condensation is something we can’t prevent because we live in a hot, humid environment. But what we can prevent is human error, and that’s where most of the water comes from. For instance, if a heat treater has their quench oil stored outside, perhaps in totes — it’s particularly important to make sure that the caps and lids on these totes or drums are very tight and secure because otherwise they’ll get condensation in there and rainwater in there.

We’ve seen instances where people are working on a furnace, and they will hit the sprinkles and the sprinklers will set off and put water into the quench oil. Heat treat furnace doors and, not so much anymore but, heat exchanges where water cooled. Anything that is under pressure is eventually going to leak and that’s why you see companies going to air-cooled heat exchangers. It’s still more difficult to get that air-cooled door and there is still some water in those doors. Like I say, anything under pressure is eventually going to leak and that’s where you see some of the water infiltration, as well.

DG: Typically speaking, how warm or how cool is the oil in a quench tank? You mentioned about condensation being caused by when it cools down, you’re going to have some condensation in there. Where do we run those tanks?

GS: It depends on if you’re using a hot oil or a cold oil. A cold oil is basically an oil that you add some heat to get it around 130-160 F, then you use your heat exchangers to keep taking the heat away when you quench the load in there. A hot oil you add heat to constantly because you want to keep that typically 250-300 F. In a hot oil, you really don’t have a lot of issues with water, unless the furnace goes down and then you get a lot more condensation than anything else. Now, cold oil, you have issues with water because you’re not above the evaporation point of the water.

DG: The bottom line is: If you’ve got too much water in the quench tank, it’s an issue.

Tell us about the measurement. How do we know if we’ve got water in there, and how do we know how much we have?

GS: Well, there are some portable test kits out there. The ones I’m familiar with are made by the Hach Company. You can purchase these from industrial supply houses like McMaster-Carr or places like that. They will give you ppm’s of water.

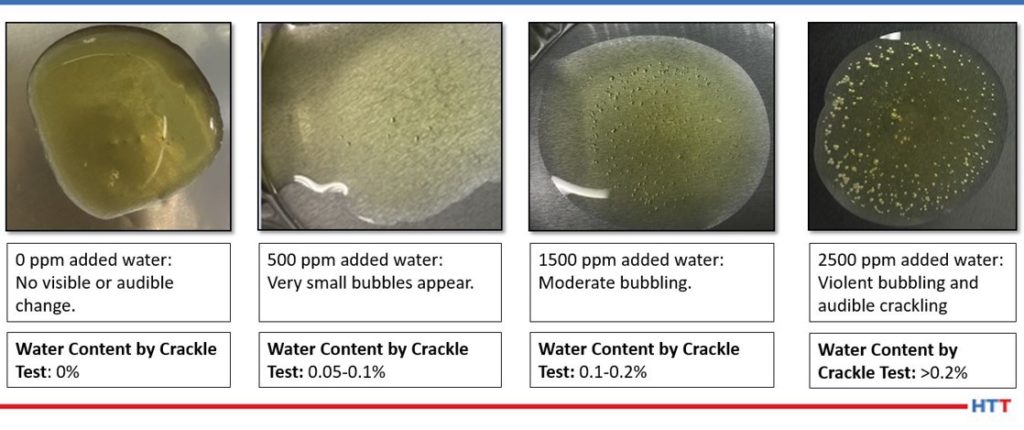

You heard a lot of old-timers always talk about crackle tests. That is not an effective way to determine how much water is in there. Our studies have shown that you can get as much as 1000-1500 ppm of water before that oil starts to crackle. The way you run a crackle test is — you take a hot panel, (that’s hotter than the boiling point of water), put a couple of drops of oil on it and if it crackles, there is water in there. Sometimes, the oil is so thick, it doesn’t really crackle, and you can’t see it until you get too much water in there.

The way all quench oil providers do it in their lab is something called a Karl Fischer titration. This is not something that the typical heat treater would have in their lab — it’s a relatively expensive piece of equipment. We use automated ones because we do so many at a time, but you can buy manual ones, if you’d like, and those are a little bit less expensive, but again, you’re talking about laboratory equipment and you’re talking about thousands of dollars instead of hundreds of dollars.

Another way to determine if you have water in your quench oil, especially on lighter colored quench oils, is to take a flashlight, put it in a clear beaker, and take a flashlight and put that flashlight at the bottom of the beaker. If nothing in that beaker is hazy and everything is very clear and amber and you can see through it, chances are there is no water in it. But if it’s a dark quench oil, like a lot of cold oils are where it’s almost jet black, the flashlight won’t do you any good.

One of our customers has talked about using a paste. Unfortunately, I don’t know the manufacturer of it, but what he did is he took a paste and put it on a wooden stick and stirred it all throughout its tank. The paste didn’t turn colors, so he knew there was no water in it. To prove that the paste was still good, he actually licked a finger and put it onto the paste and the past turned pink.

DG: This paste that you put on the stick, it doesn’t dissolve into the liquid — it’s just testing whether there is water there. And if it changes color, then you’ve got water. We’ll have to find out what that is and maybe we can put a note about that on the screen.

DG: Probably the best, most reasonable method that doesn’t cost so much, is maybe getting one of those testing kits. Do you have suggestions, Greg, on how frequently a heat treater ought to be checking his or her tank for water?

GS: I would say weekly. I don’t think it needs to be tested any more unless you think there’s a problem. If there’s a problem, obviously, test as often as you need to. But weekly is good enough.

Again, when you’re dropping a load into quench oil, you’re anywhere from 1300-1800 F, so when you drop that load in, you’re driving almost all of the water off that would be in the quench oil from condensation. It’s just if you’re worried about some sort of a human error, that’s when you want to take more frequent testing.

DG: So, it’s going to be somewhat dependent on your process.

How about the material that you are quenching? Are some materials more sensitive to water than others, or is not really an issue?

GS: Not really. It’s more of an issue of part geometry. And that goes really for distortion and cracking along with the water. A little bit of water can crack a very thin part, but on a very thick part, it may not have much effect at all.

DG: How about cosmetics? I know that some people are very concerned with cosmetics. Is water in the quench oil going to cause any issue with cosmetics, such as spotting?

GS: Short-term no, long-term yes. What causes a lot of stains is oxidation. Water, when it heats up, will actually dissociate into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen won’t oxidize the oil, but the oxygen does. That’s one of the reasons why heat treaters use flame curtains — not to allow the oxygen from the atmosphere into the furnace. At the temperatures that you heat treat at, it doesn’t take much oxygen presence to oxidize not only the parts, but also the oil.

DG: We talked briefly about why water is a problem. We talked about measuring it and trying to determine if you have an issue. Let’s move on to this: Ok, we’ve got water in the quench and it’s at an unacceptable level. What do we do?

GS: There are a few ways to do it. It really depends on what level of water you’re at, how safe you feel, and how soon do you need that furnace. Many furnaces have a bottom drain. If you turn the agitation off in the quench oil, the water is going to be heavier and denser than the oil and it will sink to the bottom. This is going to take a couple of days, at least. If you’re looking at 1000 ppm or so, this is probably the best way to do it, because then you can drain from the bottom of the tank until you no longer see water coming off and you see oil.

Let’s say you’ve got 500 ppm or 400. We recommend an upper limit of 200. For that you can run some scrap through your furnace. Again, you have to be incredibly careful because you’re not really at what would be an explosive level, but you don’t want to run good parts through there because you may get some strange hardness results — they may be higher in hardness than what you’re expecting.

Another way, (again, this will take some time), is to actually bring the temperature of your oil above the boiling point of water. If you brought it up to about 220 degrees or so, as the oil starts to evaporate, you will see bubbles and a froth (almost like a head you would see on a beer) come to the top of the oil tank. Once that’s gone, chances are your water is gone.

The last thing you can do is do a complete dump, drain, and recharge. But I would caution anybody who suspects that they have water in their quench oil, and you want to do any of this testing — before you run any loads through that furnace (with good parts), make sure you send a sample overnight to your quench oil provider and they can test it for you. That’s the biggest issue.

DG: I want to back up because you said something that I didn’t catch the fullness of, I don’t think. You said one of the solutions was to simply run scrap parts through your furnace?

GS: Yes.

DG: Now, how does that help you eliminate the water?

GS: Again, you’re taking these scrap parts and they come through your furnace and the furnace may be 1800-2200 degrees. When you dump that load into the quench, if you’ve got just a small amount of excess water, it will evaporate off.

DG: Gotcha. You’re basically bringing up the temperature of the oil so that the water evaporates.

GS: Exactly. You’re almost flashing it off.

DG: We talked about the draining and the replacing. I know of some companies recycle their oil. Any thoughts or comments about that that heat treaters ought to be aware?

GS: Yes, because that’s also a potential source of contamination for water because they skim the oil off of their cleaner tanks. I’ve been at a lot of heat treaters where they have these reclamation systems — they heat the oil up, theoretically they drive all the water off, but not always. Again, this is part of that human error. As a quench oil company, we understand that our customers are doing this, especially with oil continuing to go up. But, again, working with your quench oil supplier here is key because we’ll analyze the samples for our customers and tell them if they’re getting all that water off. Obviously, it’s in the quench oil supplier’s best interest, and the customer’s best interest, to make sure everybody is safe. If a plant burns down, nobody wins.

DG: We’ve discussed why water is a problem, how we measure it to make sure we know it, and then what to do with it. Being a quench expert, do you have any other resources, if someone was interested in learning more, whether it be specifically about water in quench oil or just other quench resources — is there anything that you can recommend for further reading?

GS: I wrote a series of articles on quench oil and how to get water out of the quench oil for your publication Heat Treat Today. Also, how to use your analysis from your quench oil supplier to operate your furnace. You should always let the data tell you how to operate a furnace and not do something just because we’ve always done it this way.

Others, such as Scott Mackenzie, have presented papers. I know back in 2018, there was a conference Thermal Processing in Motion by ASM, and he presented a paper there on how to get rid of water out of quench oil.

DG: Any other resources you’d like to recommend to people?

GS: Use your quench oil supplier. They are the experts. They’re the ones that have all of the testing equipment you need and use them as a resource. Quite frankly, if you don’t get the service from your current quench oil supplier, there are a bunch of us out there, and that’s how we distinguish ourselves — through our service — so find somebody with better service.

DG: There are a number of quench oil suppliers out there. I know some of them are not specifically targeting the heat treat market, but people still use them because they’re a local distributor or something like that.

I want to recommend to people that if you’re having trouble with the processing of parts, whether it be the mechanical properties and things of that sort, and you have a hint that it might be quench-related, it’s probably best to get ahold of people like Greg, who are actually focused in more on the heat treat market. They may have some good recommendations. This is just an encouragement to people that if you’re not using a heat treat specific quench company, there are a couple of them out there and, obviously, Greg at Idemitsu, we appreciate you giving us a little bit of expertise today.

Thanks very much, Greg. Appreciate it very much and appreciate you being with us.

GS: Thanks for your time, Doug. I appreciate the opportunity.

For more information:

Greg's phone: 919-935-9910.

Greg's email: gsteiger.9910@idemitsu.com

To find other Heat Treat Radio episodes, go to www.heattreattoday.com/radio and look in the list of Heat Treat Radio episodes listed.

Find heat treating products and services when you search on Heat Treat Buyers Guide.com

Find heat treating products and services when you search on Heat Treat Buyers Guide.com